Impacting educator motivation: Exploring the role of learning strategies in continuous professional development

MEGAN GRIFFITHS, EDUCATION DEPARTMENT, OXFORD UNIVERSITY, UK

Introduction

Continuous professional development (CPD) is widely recognised as essential for improving classroom practice and student outcomes (McCormick, 2010; Cordingley, 2015; EEF, 2021) and is a statutory requirement (Kennedy, 2016). However, educators often undervalue CPD (Teacher Tapp, 2018).

While research on student learning is well developed, less is understood about how to motivate educators in CPD (Kennedy, 2016). This discrepancy is particularly evident when comparing the innovative strategies used in classrooms with outdated CPD methods (OfstedThe Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills – a non-ministerial department responsible for inspecting and regulating services that care for children and young people, and services providing education and skills, 2024). Research suggests that CPD can be improved by using strategies that motivate educators (Kennedy, 2016). However, a gap remains in how to enhance educator motivation during CPD. Pintrich et al.’s (1991) work on learning strategies and motivation offers insights that could be adapted to CPD for educators.

This research aims to evaluate the effectiveness of CPD across roles in an Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) setting, including TAs (teaching assistants), teachers and leaders. It also seeks to improve educator motivation through learning strategies such as critical thinking, peer learning and elaboration, based on Pintrich et al.’s (1991) Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ).

Literature review

What is the current state of research on effective CPD in the context of education?

At the beginning of the 21st century, extensive research identified key elements for effective CPD, such as being research-informed, collaborative and sustained (Cordingley et al., 2007; Timperley et al., 2007; Bell et al., 2010). These reviews found that research-rich CPD improved student outcomes and teacher collaboration. However, implementation became inconsistent, partly due to austerity and resource distribution issues, leading to fragmented CPD practices across England (Cordingley, 2015).

The Department for EducationThe ministerial department responsible for children’s services and education in England standards (DfEDepartment for Education - a ministerial department responsible for children’s services and education in England, 2016) echoed earlier findings, emphasising that CPD should improve student outcomes and be evidence-based, collaborative, sustained and supported by leadership. However, studies highlight that CPD often fails to meet these standards, due to irrelevance to educators’ classroom needs and lack of follow-up activities to sustain impact (Shriki and Patkin, 2016). Recent research, such as the Education Endowment Foundation (2021) guidance, underscores the importance of motivation in CPD.

What is known about the factors that influence educator motivation in the context of CPD?

Research on educator motivation in CPD remains underexplored, but evidence suggests that motivation plays a key role (Kennedy, 2016; EEF, 2021). Surveys indicate that while many teachers regularly engage in CPD, only a minority believe that it improves teaching (Teacher Tapp, 2018). The EEF (2021) proposes three mechanisms to enhance motivation: goal-setting, credible sources and positive reinforcement.

Two case studies further highlight intrinsic motivation in CPD. Leahy and Wiliam’s (2013) Embedding Formative Assessment programme used collaborative peer learning to motivate teachers, resulting in significant student achievement gains. Similarly, Calleja (2018) found that teachers’ motivation was driven by their desire to develop teaching practices and collaborate with peers. However, limitations are that both studies focus on secondary education and overlook TAs, who play a crucial role in classrooms.

How has the concept of learning strategies been explored in CPD for educators, and what are the implications for motivation?

Learning strategies, defined as operations that learners use to make sense of information, are essential in CPD (Pintrich et al., 1991). Three strategies relevant to this research are critical thinking, peer learning and elaboration. Critical thinking involves questioning, analysing and evaluating. Pintrich et al. (1991) found that critical thinking enhances motivation. Peer learning refers to cooperative interactions, which increase motivation by fostering social acceptance. Research shows that peer learning enhances motivation when adult learners collaborate with their peers (Evans, 2022). Elaboration involves linking new information to prior knowledge, which enhances cognitive engagement and motivation. Facilitators can foster motivation by encouraging educators to actively connect new concepts to their existing knowledge base (Pintrich et al., 1991).

Methodology

This study’s sample comprised a two-form-entry school in London with 10 participants: five TAs, three teachers and two leaders. The research employed a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative and qualitative data collection (Cresswell and Piano Clark, 2007). The research included three phases, a baseline questionnaire and two research cycles, incorporating CPD sessions, pulse surveys, SLT (senior leadership team) observations and stratified interviews.

The research cycles involved two CPD sessions designed to increase educator motivation using learning strategies: critical thinking, peer learning and elaboration (Pintrich et al., 1991). These sessions focused on high-quality interactions in the EYFS and were followed by pulse surveys and SLT observations to measure impact.

Pulse surveys, based on Pintrich et al.’s MSLQ (1991), were used to capture immediate impacts on motivation. SLT observations provided additional insights, although limited by time constraints, and helped to evaluate the sustained impact of the intervention. Stratified interviews with selected participants provided deeper qualitative insights into the factors influencing motivation. A codingIn qualitative research, coding involves breaking down data into component parts, which are given names. In quantitative research, codes are numbers that are assigned to data that are not inherently numerical (e.g. in a questionnaire the answer 'strongly agree' is assigned a 5) so that information can be statistically processed. frame was used to analyse the data, ensuring consistency and validityIn assessment, the degree to which a particular assessment measures what it is intended to measure, and the extent to which proposed interpretations and uses are justified (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

Collaboration with colleagues and SLT was integral throughout, enhancing the study’s design and ensuring that it aligned with school priorities. Ethical considerations followed BERA guidelines (2024), including confidentiality and minimising participant burden.

Findings and discussion

In the baseline questionnaire, all 10 participants reported feeling motivated in their roles, yet nine expressed dissatisfaction with current CPD. This indicates that while educators are motivated in their teaching roles, the existing CPD structure is demotivating.

Participants highlighted several factors that would improve motivation in CPD: evidence-based CPD or qualifications (n = 5), engaging strategies (n = 8) and relevance to their classroom practice (n = 4). Time-related issues (n = 7) and irrelevant content (n = 3) were cited as demotivating factors.

Is there empirical evidence demonstrating the impact of learning strategies on educator motivation in the context of professional development and if so which strategy proves most effective?

The analysis of pulse surveys, stratified interviews and SLT observation data provided insights into the impact of learning strategies on educator motivation. Quantitative methods, such as ANOVA, were used to assess how these strategies influenced motivation, considering variables such as role and experience.

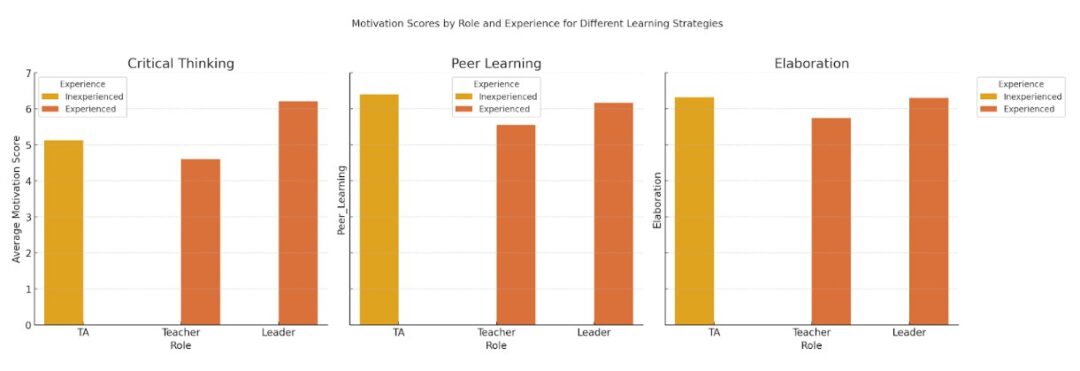

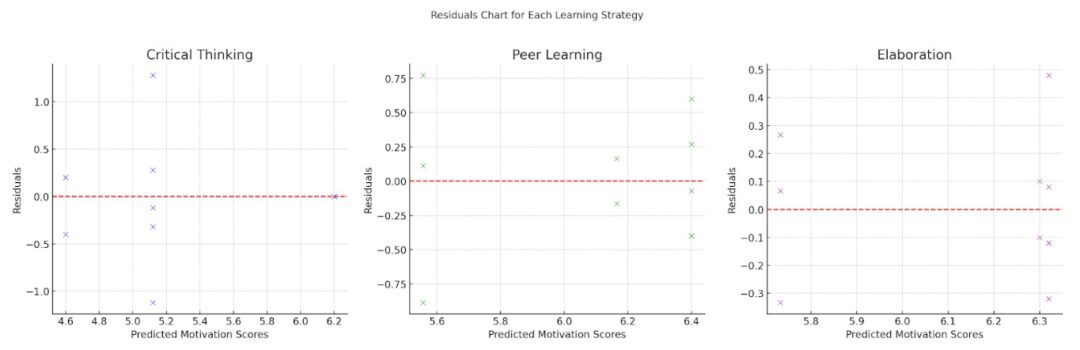

Pulse surveys were administered after each CPD session to measure the effects of different learning strategies on motivation. The bar chart in Figure 1 displays mean motivation scores and the residuals chart in Figure 2 visualises motivation in relation to role and experience for each learning strategy.

Figure 1: Motivation scores by role and experience for different learning strategies

Figure 2: Residuals chart for each learning strategy

The findings show that learning strategies positively influenced educator motivation, although the degree of motivation varied depending on educators’ roles and experience.

Critical thinking: ANOVA analysis revealed a significant interaction between role and experience for critical thinking, suggesting that its effectiveness is influenced by these factors. More experienced educators, particularly those in leadership, were more motivated by critical thinking tasks. The residuals chart supported this, showing a random distribution around the zero line, indicating a good model fit and reinforcing the observed relationship between role, experience and motivation.

Peer learning: The analysis showed no significant interaction effects between role and experience, suggesting that peer learning had a uniform impact across all educator groups. The residuals chart further supported these findings, with no discernible patterns. Peer learning proved to be a robust learning strategy across various roles and experience levels.

Elaboration: The interaction between role and experience approached significance in the ANOVA analysis, suggesting a potential trend. However, the data was insufficient to draw firm conclusions, and elaboration was used only in the first research cycle. The residuals chart suggested a reasonable model fit, but further research is needed to assess elaboration’s impact on motivation.

The evidence suggests that while all learning strategies positively influenced educator motivation, their effectiveness varied depending on the educators’ roles and experience. Critical thinking was most effective for experienced educators, while peer learning had a consistent impact across all groups. Elaboration showed potential but requires further investigation with a larger sample size.

When comparing this study’s motivation scores with Pintrich et al.’s MSLQ (1991), the scores for critical thinking and peer learning were higher in this intervention. Educators in this study were more motivated by critical thinking and peer learning, likely due to their professional maturity. Elaboration, while effective, showed similar motivation scores to those reported by Pintrich et al. (1991), but further research is needed to confirm.

Stratified interviews provided qualitative data to supplement the empirical findings. Critical thinking was mentioned by one out of three interviewees, with a leader citing it as a motivating factor. Peer learning received the highest frequency of mentions, with two educators noting its role in enhancing motivation. Elaboration, although mentioned less frequently, was described as helpful for reframing thoughts and supporting other learning strategies.

SLT observations, conducted two weeks after the first CPD session, indicated an increase in motivation across all roles. New knowledge had been regularly incorporated into classroom practice, with SLT noting informal discussions among staff around CPD topics. However, the short observation period and incomplete data limited the ability to measure long-term impact.

Conclusion

The findings confirm that learning strategies such as critical thinking, peer learning and elaboration positively impact educator motivation, although their effectiveness varies by role and experience. Critical thinking was found to be most effective for experienced educators, while peer learning had a positive effect across all roles. Elaboration showed promise but lacked sufficient data for conclusive results.

Beyond learning strategies, participants identified other motivators: research-informed CPD, active learning and constructive feedback. Research-based CPD from trusted sources, like the EEF, was highly valued, while active learning enhanced motivation during sessions. Coaching-based feedback was also seen as essential for sustaining CPD impact.

Professional recommendations for CPD

- Integrate critical thinking activities for experienced educators

- Incorporate peer learning across sessions

- Ensure that CPD content is research-informed

- Use active learning strategies to engage participants physically and mentally

- Adopt coaching-based feedback to sustain CPD impact

- Promote facilitators’ ongoing growth to keep CPD motivating and relevant.

- Bell M, Cordingley P, Isham C et al. (2010) Report of professional practitioner use of research review: Practitioner engagement in and/or with research. CUREE, GTCE and LSIS. Available at: www.curee.co.uk/files/publication/1297423037/Practitioner%20Use%20of%20Research%20Review.pdf (accessed 8 November 2024).

- Braun V and Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2): 77–101.

- British Educational Research Association (BERA) (2024) Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research, 5th ed. Available at: www.bera.ac.uk/publication/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-fifth-edition-2024 (accessed 2 August 2024).

- Calleja J (2018) Teacher participation in continuing professional development: Motivating factors and programme effectiveness. Malta Review of Educational Research 12(1): 5–29.

- Cordingley P (2015) The contribution of research to teachers’ professional learning and development. Oxford Review of Education 412: 234–252.

- Cordingley P, Bell M, Isham C et al. (2007) Continuing Professional Development (CPD): What do specialists do in CPD programmes for which there is evidence of positive outcomes for pupils and teachers? EPPI-Centre. Available at: https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Portals/0/PDF%20reviews%20and%20summaries/CPD4%20Report%20-%20SCREEN.pdf?ver=2007-09-28-142054-167#:~:text=Specialists%20supported%20teachers%20through%20modelling,and%20providing%20feedback%20and%20debriefing (accessed 8 November 2024).

- Cresswell JW and Piano Clark VL (2007) Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Department for Education (DfE) (2016) Standards for teacher professional development. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a750b16ed915d5c54465143/160712_-_PD_Expert_Group_Guidance.pdf (accessed 8 November 2024).

- Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) (2021) Effective professional development. Available at: https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/education-evidence/guidance-reports/effective-professional-development (accessed 8 November 2024).

- Evans L (2022) Doubt, skepticism, and controversy in professional development scholarship: Advancing a critical research agenda. In: Menter I (ed) The Palgrave Handbook of Teacher Education Research. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, pp. 451–476.

- Kennedy MM (2016) How does professional development improve teaching? Review of Educational Research 86(4): 945–980.

- Leahy S and Wiliam D (2013) Embedding Formative Assessment. Schools, Students and Teachers network (SSAT). Available at: www.ssatuk.co.uk/cpd/teaching-and-learning/embedding-formative-assessment (accessed 8 November 2024).

- McCormick R (2010) The state of the nation in CPD: A literature review. The Curriculum Journal 21(4): 395–412.

- Ofsted (2024) Independent review of teachers’ professional development in schools: Phase 1 findings. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/publications/teachers-professional-development-in-schools/independent-review-of-teachers-professional-development-in-schools-phase-1-findings#fn:3 (accessed 8 August 2024).

- Pintrich PR, Smith DAF, Garcia T et al. (1991) A manual for the use of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ). Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED338122.pdf (accessed 8 November 2024).

- Shriki A and Patkin D (2016) Elementary school mathematics teachers’ perception of their professional needs. Teacher Development 20(3): 329–347.

- Teacher Tapp (2018) What teachers tapped this Week #56 – 22nd October 2018. Available at: https://teachertapp.co.uk/articles/what-teachers-tapped-this-week-56-22nd-october-2018 (accessed 8 November 2024).

- Timperley H, Wilson A, Barrar H et al. (2007) Teacher professional learning and development: Best Evidence Synthesis iteration (BES). New Zealand Ministry of Education. Available at: www.educationcounts.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/16901/TPLandDBESentireWeb.pdf (accessed 8 November 2024).