Addressing normativity in teaching: My reflections on professionalism as a black assistant headteacher at a British school

FOLA ADEKOLA, ASSISTANT HEADTEACHER, EDMONTON COUNTY SCHOOL, UK; DOCTORAL STUDENT, UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON, UK

I arrived in the UK in 2005, with a teaching degree from Nigeria, as an ambitious young woman who had graduated top of my class in the university and rarely doubted my competence or capabilities. I was relatively confident (or so I thought).

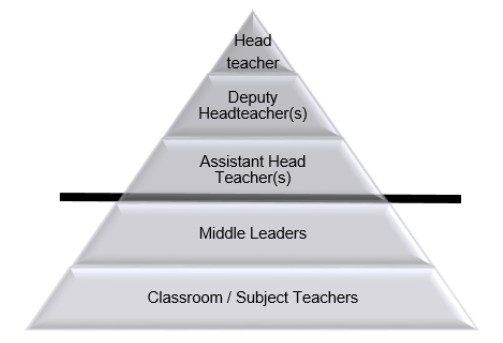

I secured a teaching job at a multicultural school and was soon astounded by the under-representation of people of colour in the senior leadership team (SLT), despite the diversityThe recognition of individual differences in terms of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, physical ability, religious beliefs and other differences of the student population. I have designed Figure 1 to represent my view of the structure of school leadership at the British schools around me. I have added the black line at the point of entry to SLT, where there appears to be a barrier for people who are non-white.

Figure 1: Structural representation of the hierarchy of school roles at my school

According to the school workforce census published by the Department for EducationThe ministerial department responsible for children’s services and education in England in 2023, white British made up 85.1 per cent of the entire teaching workforce. However, 92.5 per cent of headteachers, 90.8 per cent of deputy headteachers and 87.8 per cent of assistant headteachers were white British.

From the statistics, it is a fact that white teachers are over-represented in leadership posts in English schools. What is the reason for this over-representation? What is the impact of the ‘whiteness’ of leadership in schools on what we regard as professionalism?

Possible barriers to SLT

1. Discriminatory recruitment practices

Years of research activities have continued to produce evidence of discriminatory practices in relation to the progression of black staff at work. For example, in research conducted by Grummell et al. (2009) into the appointment of senior leaders in education, some of the criteria used to select candidates included the use of ‘local logics’ – which is when a school values the selection of a leader who would be a ‘comfortable fit’. My question is how does a potential employer determine how you fit into the school without an unconscious bias towards the familiar and normativity? Is it tempting to recruit candidates who have familiar qualities (like the norm)?

2. The experience of super-surveillance

Puwar (2004) argues that in many institutions whiteness and white people are viewed as the accepted ‘norm’ and therefore are more likely to occupy privileged positions within these spaces. Women and minorities are seen as disruptors to these spaces and are therefore under a form of super-surveillance, where their every gesture, movement and utterance is observed. The effect of super-surveillance can mean that, for example, black middle leaders are overlooked for promotion due to being constantly under the spotlight, where any mistakes that they have made in the past are amplified and they are unjustly seen as less competent than their white counterparts.

3. The experience of micro-aggressions and low self-confidence of black teachers

One of the impacts of normativity is ‘micro-aggressions’ – a term used to describe how covert racism can take place in the workplace (Marom, 2018). These subtle forms of racism are difficult for people of colour to challenge, for fear of being labelled ‘aggressive’ (Sharp and Aston, 2024).

Unfortunately, years of exposure to continuous micro-aggression can lead to internalised oppression, as discovered in research conducted by Steele and Aronson (1995), where participants judged both themselves and their students as inadequate. After years of experiencing micro-aggressions, it is possible for some black teachers to self-reject and consider themselves ‘inadequate’ to become SLT.

The under-representation of black leaders in the profession can have a detrimental effect on the self-confidence and career aspirations of young teachers, setting up further barriers. Bariso (2001, p. 177) highlights various factors – for example, racism, low expectations, stereotypes, exclusion, low pay, lack of promotion, lack of encouragement – that can act as obstacles to non-white teachers and combine to create a sense of ‘deprofessionalisation’. In turn, this cumulative barrier of ‘deprofessionalisation’ can lead black and minority ethnic teachers to feel a lower sense of professional confidence than their white peers.

What could be done to address normativity in teaching?

Although change to the racial hierarchy in the teaching profession in the UK will be difficult to achieve, the activist professional in me longs for change by questioning and challenging values and beliefs.

To address this normativity, my suggestions are:

- Intentional efforts by the UK government to require schools to have diverse leadership teams: In a world where schools are driven by targets, without making a diverse leadership team a key performance indicator, schools are unlikely to act. One could argue that this could lead to positive discrimination. However, as there will be benefits to having a diverse team, it is a risk worth taking. As a black leader, I welcome the idea of being part of a diverse team.

- Fairer recruitment practices: The introduction of blind/anonymised application forms could be used at the initial application stage, particularly for leadership posts. Research suggests that candidates with non-white names are unlikely to be invited to interview (Carthen, 2014). In addition to this, schools could be expected to publish/report on the ethnicity of applicants who applied and those appointed, to foster transparency in recruitment practices.

- Regular training for all teachers including school leaders: I have worked with a number of colleagues who lacked cultural awareness and didn’t notice the micro-aggressions present in the nuances of their actions. As safeguarding training is required to work in school, so should a training programme on working in a diverse community be delivered.

Conclusion

I question whether being a professional in the UK is beyond acquiring qualifications, as certain doors are closed due to the colour of your skin. This is the daily reality for many black teachers, as the face of teacher professionalism – especially that of SLT – remains disproportionately white.

From my own reflection, anecdotal evidence and my perception of the experiences of my black colleagues, black teachers continue to experience discrimination. Teacher professionalism in the UK is highly subjective and heavily influenced by white normativity. What can you do about it?

- Bariso E (2001) Code of professional practice at stake? Race, representation and professionalism in British education. Race Ethnicity and Education 4(2): 167–184.

- Carthen TM (2014) Ethnic names, resumes, and occupational stereotypes: Will D'Money get the job? Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects, paper 359. Available at: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/214118534.pdf (accessed 26 November 2024).

- Department for Education (DfE) (2023) School teacher workforce. Available at: www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/workforce-and-business/workforce-diversity/school-teacher-workforce/latest#full-page-history (accessed 26 November 2024).

- Grummell B, Devine D and Lynch K (2009) Appointing senior managers in education: Homosociability, local logics and authenticity in the selection process. Educational Management Administration & Leadership 37(3): 329–349.

- Marom L (2018) Under the cloak of professionalism: Covert racism in teacher education. Race Ethnicity and Education 22(3): 319–337.

- Puwar N (2004) Space Invaders: Race, Gender and Bodies Out of Place. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Sharp C and Aston K (2024) Ethnic diversity in the teaching workforce: Evidence review. NFER. Available at: www.nfer.ac.uk/publications/ethnic-diversity-in-the-teaching-workforce-evidence-review (accessed 26 November 2024).

- Steele CM and Aronson J (1995) Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69: 797–811.