Criticality in evidence-informed teaching: Expansive learning with Rosenshine

CHRISTIAN BOKHOVE AND ROSALYN HYDE, UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON, UK

As educators, we have noticed that there is sometimes an uncritical adoption of evidence since what some have called an ‘evidence-informed revolution’. A case in point can be found in the work of Barak Rosenshine, which has been extremely influential in schools, especially in the context of early career teachers (ECTs). The work is also included as ‘key reading recommendation’ in the Initial Teacher TrainingAbbreviated to ITT, the period of academic study and time in school leading to Qualified Teacher Status (QTS) and Early Career Framework (DfEDepartment for Education - a ministerial department responsible for children’s services and education in England, 2024). Our stance is that in embracing evidence-informed practices, we need to critically engage with the sources of evidence with which we are presented. For novice teachers, developing the necessary criticality to do this is a challenge, but one that cannot be put off and not something that happens automatically. This perspective piece explores the nature of Rosenshine’s evidence and suggests that criticality regarding evidence can be developed and enhanced by Engeström’s expansive learning cycle.

The work of Rosenshine

Most teachers will encounter Rosenshine’s work through two main publications that have become popular. The most well-known one is Rosenshine’s 2012 article for American Educator, the magazine of the American Federation of Teachers, which we will refer to as AFT. The article presents ‘principles of instruction’, which the author describes as ‘research-based strategies that all teachers should know’. The text of the article is similar to a booklet that Rosenshine published with UNESCO (Rosenshine, 2010).

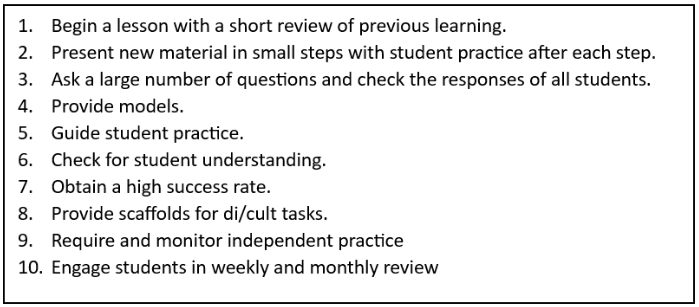

Figure 1: Ten principles from Rosenshine (2012)

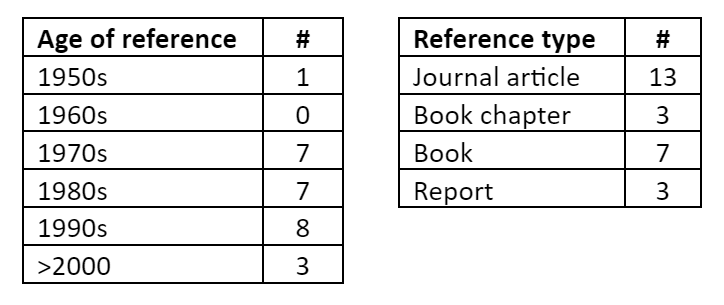

Although both publications contain boxes with 17 principles, explanations are only provided for the 10 principles presented in Figure 1. According to the more popular AFT article, the list of 17 principles ‘overlaps with, and offers slightly more detail than, the 10 principles used to organize that article’ (p. 19). Collectively, the two publications reference 26 unique sources, the breakdown of which is shown in Table 1. Very few references can be called contemporary.

Table 1: References in Rosenshine’s work

The oldest reference is the famous article from the 1950s on ‘the magical number seven’ by Miller (1956) in relation to the limitations of working memory. Of course, nothing of this ostensibly is necessarily problematic, but for teachers, it’s important to be aware of the fact that the work mainly cites more than 25-year-old research. An example where this might be problematic is when recent insights have changed. For example, Rosenshine cites Sweller (1994), but in a recent commentary, Sweller (2023) describes how much cognitive load theoryAbbreviated to CLT, the idea that working memory is limited and that overloading it can have a negative impact on learning, and that instruction should be designed to take this into account has changed over the decades. In other words, we can’t assume that the insights from 30 years ago still apply. This also shows why age does matter in some cases: small, unrepresentative sample sizes can lack statistical power (Fan, 2001).

Following up references

One challenge in appraising Rosenshine is that in many ways the articles do not conform to normal conventions in the scientific literature, namely that you reference a claim where the claim is made. The 10 principles are each only accompanied by two or three references at the end of the sections. This makes it virtually impossible to trace back the origins of the principles. This is already challenging with a journal article or book chapter, but even more so with whole books being cited. But even when one can follow up references, it is not always clear where a principle comes from. There is no doubt that some of the studies referenced are impressive in many ways. The studies are ambitious in scope and intent, and they certainly cover many of Rosenshine’s points. However, many principles are also rather underspecified. Take the role of ‘feedback’. One of the 17 principles is ‘Provide systematic feedback and corrections’. But where does ‘feedback’ sit among these principles? The only two occurrences of the word ‘feedback’ in the AFT article are in the context of peer feedback and on feedback during student practice. There’s not much to go on here: it can mean everything to everyone, something that might actually contribute to its appeal. Another example in the AFT article concerns the now very popular ‘80 per cent correct’ for the principle about ‘obtaining a high success rate’. Rosenshine (2012) himself writes that ‘In a study of fourth-grade mathematics, it was found that 82 percent of students’ answers were correct in the classrooms of the most successful teachers, but the least successful teachers had a success rate of only 73 percent.’ (p. 17) But on tracing down the original source of the citation in Rosenshine’s article, the different success rates were actually closer to 83 per cent and 76 per cent (Good and Grouws, p. 51). Although still a statistically significant difference, it seems a small one with which to distinguish between minimally and highly effective teachers. We are in a quandary: on the one hand, we want to provide ECTs with concrete recommendations like ‘80 per cent success’; on the other hand, we want ECTs to be critical consumers of evidence. How can we potentially square this circle?

Developing evidence-informed teachers

We suggest that those working with teachers at the beginning of their careers have an important role to play in helping trainee teachers and ECTs to make sense of the educational landscape. We believe that it is important that ECTs develop the skills to understand, evaluate, critique and apply research and evidence in their classrooms. Such skills support longevity in the classroom by helping teachers to be thoughtful and reflective professionals, able to problem-solve and to be responsive to developments in teaching and in education policy. We have been working for some time on the Research in Teacher Education project (RiTE, www.rite-project.eu), which aims to promote and facilitate teachers to create evidence-informed teaching practice. The results from the project (www.rite-project.eu/results) indicate that participants developed a better understanding of what constituted evidence and of evidence-informed practice. The project also found that a deeper understanding of evidence can enhance practice and decision-making in teaching. However, participants felt that they faced challenges in implementing such practices. These included a lack of time and a lack of availability of clear-quality criteria for assessing evidence. They also felt that they had a low status in school as a beginning teacher, meaning that they were dependent on their mentors and therefore less able to challenge existing views. Key recommendations from the project emphasise the importance of reflecting on evidence and evidence-informed practice. The process outlined here is one that would support ECTs in developing a more critical approach to innovations and trends in education.

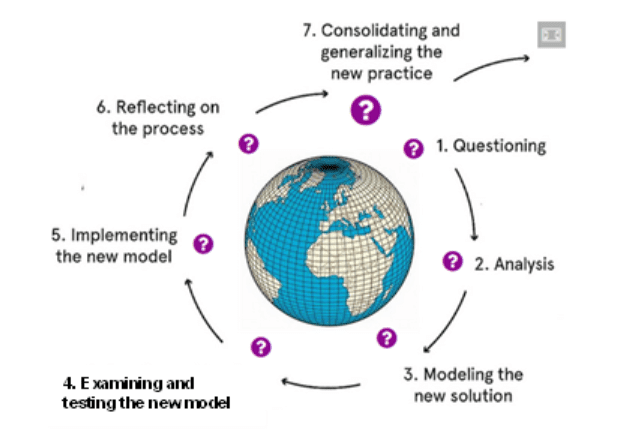

In our initial teacher education (ITE), we adopted the ‘expansive learning cycle’ by Engeström and Sannino (2010), featured in Figure 2. In expansive learning, ‘learners learn something that is not yet there’ (p. 2), which seems especially appropriate for teachers just starting out.

Figure 2: Sequence of learning actions in an expansive learning cycle (adapted from Engeström and Sannino, 2010)

We elaborate on the steps in the expansive learning cycle in the context of ECTs, using the case of Rosenshine and drawing on our experiences from the RiTE project.

Steps 1 and 2: Questioning and analysis

Identify an issue to work on. In the context of this article, this might be one of Rosenshine’s principles that you want to know how to implement in your own context. Find a range of evidence about this issue. The evidence can come from a range of sources and should include contrasting views. The Impact journal and the Education Endowment Foundation website are both good starting points for this. As you examine the evidence, ask yourself questions about the quality of the evidence, the standpoint of the author, the audience for the evidence and how it links to learning theories and consider how convinced you are by it in the context of what you know from your own practice. Our trainee teachers learned how to do this and reported that they regularly found that evidence was tentative but that learning how to interrogate evidence was a powerful skill in transforming their classroom practice.

Step 3: Modelling the new solution

In this step, plan a small classroom-focused empirical inquiry. Using the evidence from steps 1 and 2, identify a small practical change that you can make to your practice. We have found that this works best with a focus on a single class, a specific change and over a defined, manageable timescale (for example, a few weeks).

Step 4: Examining and testing the new model

Here, your ECT mentor or another colleague can provide feedback on your plan. You will also need to decide what type of data you need to collect in order to find out what impact the change has had on your practice and student learning. Our trainee teachers found that pre- and post-testing and trying to match the intervention group against a control group were not fruitful for this type of study. We encouraged them to use the data and information that they already had available and to build the data-collection into their teaching – for example, by using student work, lesson observation, their own notes, short written comments from students, etc.

Step 5: Implementing the new model

You will now be ready to implement your plan within your classroom practice and to collect some data. Collect the data in a structured way. Analysing this data is important, so that you can evaluate the impact of your inquiry.

Step 6: Reflecting on the process

The survey and interview data from the RiTE project identified that reflection was key to implementing evidence-informed practice, so it is important to take the time to carry out this stage. This is also a point where your ECT mentor or another colleague can provide a sounding board to help you to do this.

Step 7: Consolidating and generalising the new practice

The next stage is to consider the implications of your inquiry. You might like to consider how you can develop this aspect of your practice further or how you can apply your learning to another class or another context. In the RiTE project, our trainee teachers applied their learning to a different context as part of their teacher training programme.

The process could also lead to renewed questioning (step 1), creating a positive feedback loop of criticality and improvement. Our trainee teachers identified this cyclical process as powerful and as leading to them adopting more evidence-informed practices in their classroom teaching. This was a model that they also felt that they would be able to use as they became ECTs, in order to develop their practice and solve problems in their classrooms using an evidence-informed approach. It also provides a way in which to take an idea or proposition, such as one of Rosenshine’s principles, to consider critically some of the evidence base and then to shape that into an inquiry that will impact on practice, through considering context and being specific. We very much support the move towards an even more evidence-informed profession. However, in doing so, we should not just adopt and accept the evidence-informed ideas that we are offered, but show criticality as well, a hallmark of being evidence-informed.

We thank the trainees for their participation and the EU for the Erasmus+ funding for the RiTE project (101507).

- Department for Education (DfE) (2024) Initial teacher training and early career framework. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/publications/initial-teacher-training-and-early-career-framework (accessed 26 June 2024).

- Engeström Y and Sannino A (2010) Studies of expansive learning: Foundations, findings and future challenges. Educational Research Review 5(1): 1–24.

- Fan X (2001) Statistical significance and effect size in education research: Two sides of a coin. The Journal of Educational Research 94(5): 275–282.

- Good TL and Grouws DA (1977) Teaching effects: A process-product study in fourth-grade mathematics classrooms. Journal of Teacher Education 28(3): 49–54.

- Miller GA (1956) The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological Review 63(2): 81–97.

- Rosenshine B (2010) Principles of Instruction. UNESCO International Bureau of Education. Available at: https://orientation94.org/uploaded/MakalatPdf/Manchurat/EdPractices_21.pdf (accessed 26 June 2024).

- Rosenshine B (2012) Principles of instruction: Research-based strategies that all teachers should know. American Educator 36(1): 12–19, 39.

- Sweller J (1994) Cognitive load theory, learning difficulty, and instructional design. Learning and Instruction 4(4): 295–312.

- Sweller J (2023) The development of cognitive load theory: Replication crises and incorporation of other theories can lead to theory expansion. Educational Psychology Review 35: 95. DOI: 10.1007/s10648-023-09817-2.