Designing a trust-wide professional development programme

RICHARD HARVEY-SWANSTON, SENIOR LECTURER, UNIVERSITY OF BRIGHTON, UK

KERRI BURNS, SCHOOL IMPROVEMENT ADVISOR, UNIVERSITY OF BRIGHTON ACADEMIES TRUST, UK

TIFF COLE, FACULTY LEAD COACH, UNIVERSITY OF BRIGHTON ACADEMIES TRUST, UK

Introduction

Teacher professional development (PD) is a critical factor influencing student outcomes (Cordingly, 2015) and teacher retention (EEF, 2023). While research has extensively explored the characteristics of effective PD, the process of translating evidence into actionable PD design remains under-investigated. This case study addresses this gap by reporting our approach to designing evidence-based PD for middle leaders at the University of Brighton Academies Trust (UoBAT), a group of 14 infant, primary and secondary academies spanning East and West Sussex.

Our brief was to design, implement and evaluate PD for newly established subject leader groups (‘faculties’), with the aims of improving subject leadership, student outcomes and cross-trust collaboration, and form part of a wider strategy to enable colleagues to develop sustainable, self-leading and evidence-informed professional learning communities. UoBAT academies serve a range of different communities and face different challenges. Consequently, our trust strategy identifies key common priorities while seeking to value and foster the individual character of each academy. We see the significance of context also reflected in the application of research to practice where generalisability is challenging; what works well in one setting is not guaranteed to do so in another. For us, applying evidence to practice is less about enacting research insights or selecting well-trialled PD models (e.g. Lesson Study) and more about understanding how our strengths, needs and contextual parameters connect with the existing research literature so that we might best judge what ‘appropriate’ means for us now and in the longer term.

Balancing aims

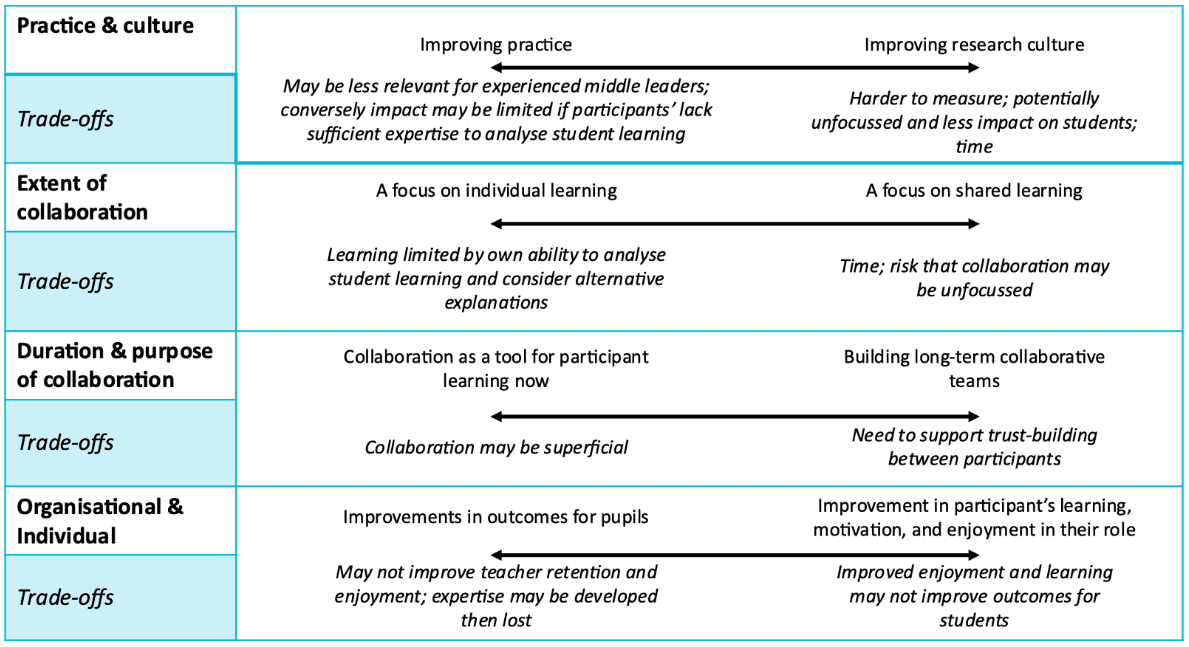

During the initial design phase, we explored how we might emphasise potential aims and the trade-offs that these involved (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Making sense of PD aims

Research reviews identify components of effective PD (e.g. Cordingly, 2015) and emphasise how these elements interconnect with each other and with participant context (e.g. Timperley et al., 2007). We found that this interconnectedness made decision-making difficult: choosing to focus on one aim had implications for others, and mitigating actions, in turn, had further effects. For instance, it seems reasonable to seek to improve both practice and research culture – they are not mutually exclusive and both these aims are well supported by PD research. However, we cannot prioritise all potential goals, and balancing them has implications for practice and measurement of impact. Mapping trade-offs supported us to establish the relative focus that we might place on each and to begin to discuss what might indicate that an improvement had been made.

Collaborative problem-posing

Mapping potential aims and trade-offs enabled us to begin interpreting the research, judging which design elements might be appropriate. This helped us to identify a broad model of cycles of practitioner enquiry. Selecting PD elements is just the start of the design process, raising practical questions and decisions, particularly about who decides the PD focus. We might have opted for a top-down approach of selecting a strategic priority for participants to address. Or we might have given them free reign to choose any topic of interest to them (bottom-up). Both approaches are problematic. A bottom-up approach might establish buy-in, but managing multiple disparate lines of enquiry has knock-on effects for collaboration (perhaps less purposeful if participants are addressing very different issues) and for resourcing. Similarly, PD based on organisational priorities may divert attention from more impactful learning for individuals in the long term.

We found Swann’s (2012) problem-based methodology particularly valuable in understanding how problem-posing could also have a role in professional learning. Swann (2012) argues that problems are not simply identified but created, and multiple problems can be formulated from a single situation. For instance, a lack of participation in paired/group discussion by lower-attaining students might be framed as a problem relating to equitable dialogue (perhaps leading to scaffoldingProgressively introducing students to new concepts to support their learning of dialogue) or relating to prior knowledge (perhaps leading to scaffolding of prior knowledge) or something else altogether. In formulating a problem, an individual therefore (at least partially) exposes their values and their working model of the relationship between teaching and learning, making this visible to others and therefore possible to examine and learn from.

Shared noticing

Theories of teacher noticing (e.g. Mason, 2002) connect with our focus on problem-formulation because the course of action intended to improve a problem is not guaranteed to do so, and when analysing its impact (in our case via classroom video data), the potential learning for the participant is limited by what they notice and their interpretation of its significance. Thus, the concept of noticing grants us a sense of the potential mechanism for learning and a clearer understanding of the practical value of collaboration: others may bring to attention what you did not notice or attribute it to different causes, either of which has the potential to develop participants’ working models.

Conclusion

Consequently, our PD centres on the following design elements:

- facilitated formulation of participants’ own problems, based on detailed analysis of learning in their academies

- exploring and selecting actions to improve their problem, based on all available evidence, and stating predictions of what specifically will change

- analysing video of the selected improvement action and its impact on students’ learning in context, and collaborative dialogue that reviews what is noticed, the accuracy of their predictions and its implication for participants’ own learning and leadership of their subject

- sustained enquiry through repeated cycles of analysis.

Initial data indicates clear improvements in participants’ expertise and cross-trust collaboration. A key finding in relation to the impact of the PD design is evidence of the way in which the three design elements interact to create impact. Problem formulation exposed participants’ knowledge to others because it required them to explain why a situation is problematic. When combined with collaborative dialogue, it created a space for learning where others could pose different ways of framing the problem, predicting consequences of changes to practice and interpreting events in a lesson video. Importantly, this led to improvements in expertise related to local priorities, without adding additional work or activity.

Ultimately, our approach was about interpreting rather than applying research evidence to PD design, which can be summarised as:

- Engaging with evidence of effective PD: This was not with a view to simply apply those research findings, but rather to arrive at a point where we were able to judge what evidence might be appropriate in a trust-wide context

- Mapping context, potential aims and trade-offs: Rather than thinking along the lines of dichotomies (top-down, bottom-up), we prioritised design elements that seemed likely to support participants to learn through tackling priorities in their academies

- Designing an evaluation approach from the outset: Careful consideration of how outcomes might be measured enabled us to set clear, achievable goals.

- Cordingley P (2015) The contribution of research to teachers’ professional learning and development. Oxford Review of Education 41(2): 234–252.

- Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) (2023) Teacher quality, recruitment and retention: Rapid evidence assessment. Available at: https://d2tic4wvo1iusb.cloudfront.net/production/documents/Teacher-quality-recruitment-and-retention-lit-review-Final.pdf?v=1720530848 (accessed 10 July 2024).

- Mason J (2002) Researching Your Own Practice: The Discipline of Noticing. London: Routledge.

- Swann J (2012) Learning, Teaching and Education Research in the 21st Century: An Evolutionary Analysis of the Role of Teachers. London: Continuum.

- Timperley H, Wilson A, Barrar H et al. (2007) Teacher professional learning and development: Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration (BES). Wellington: Ministry of Education. Available at: www.educationcounts.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/16901/TPLandDBESentireWeb.pdf (accessed 10 July 2024).