Developing staff professionalism through leading a culture of learning

MELANIE CHAMBERS, DIRECTOR OF PROFESSIONAL LEARNING, THE BRITISH SCHOOL OF BRUSSELS, BELGIUM

MELANIE WARNES, FORMER PRINCIPAL AND CEO, THE BRITISH SCHOOL OF BRUSSELS, BELGIUM

EMMA ADAMS, PROFESSIONAL LEARNING CO-ORDINATOR AND RESEARCH LEAD, THE BRITISH SCHOOL OF BRUSSELS, BELGIUM

This case study examines leadership decisions and actions at the British School of Brussels (BSB) to develop a ‘learning organisation’ (Kools and Stoll, 2016). BSB is a non-selective, all-through international school, with 1,350 students from 70 nationalities, aged one to 18, and 350 staff. Over eight years, BSB has transformed into a thriving learning organisation. Key enabling principles at BSB align with the Chartered College of Teaching working paper ‘Revisiting the notion of teacher professionalism’ (Müller and Cook, 2024), both recognising the value of staff autonomy, agency and voice, underpinned by trust.

It is well documented that a school’s culture and sub-culture relate to its effectiveness (Hargreaves, 1994; Stoll and Fink, 1989; Rosenholtz, 1989). Within our setting, we believe that, as professionals, the most valuable resource that we have is each other, and we can learn from one another irrespective of our positions in the school. Hargreaves and Fullan (2012, p. 112) recognise that ‘teachers who work in professional cultures of collaboration tend to perform better than teachers who work alone’ and, similarly, we have witnessed that where a school culture values humanity and collaborative approaches to staff learning, it fosters belonging and commitment. BSB’s Professional Learning Community (PLC) is a ‘whole-school model’ (Harris et al., 2018), led by teaching and operational staff and students. The PLC values inquiry and collaboration to develop collective professionalism. We have witnessed how such a culture thrives when leadership emphasises peer-to-peer accountability over traditional hierarchical models.

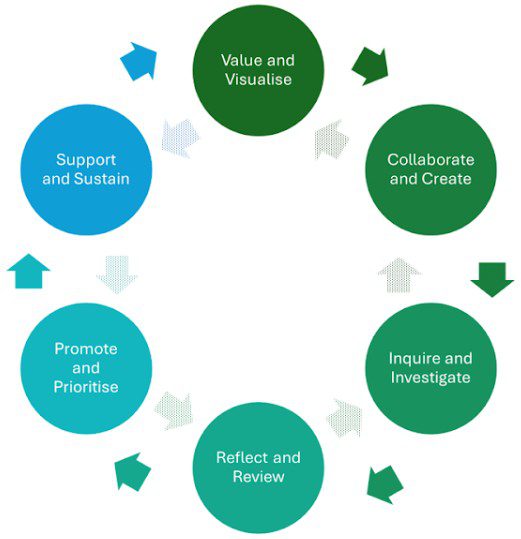

Supporting staff through a process of change has required both implicit and explicit actions. We have developed a clear professional learning leadership model (Figure 1), enabling learning at all system levels: learning for oneself, others and the whole organisation. Sharing this model with staff improves professional learning initiatives, making them explicit. We have used it at an individual, team and whole-school level to add clarity to strategy. This case study is organised around the themes of this model and gives examples of actions taken at a whole-school level. It is important to note that although set out in a linear fashion, there are moments when steps must be revisited, represented by anticlockwise arrows.

Figure 1: Developing and leading professional learning at BSB

Value and visualise

Fullan (2011) emphasises that leadership is about helping people to find meaning. At BSB, the first step in creating a PLC was aligning our community around a set of co-created core values, known as the guiding statements. This process involved the entire community and took a year to complete. The guiding statements articulate actionable values for all our community and guide daily interactions, teaching, recruitment and curriculum, serving as the compass for our PLC.

Feedback from our staff surveys has underlined the role of trust in developing the conditions for a PLC. We believe that trust is necessary at both personal and professional levels for fostering innovation and growth of expertise, and that the absence of trust limits individual buy-in, stifling innovation and creativity.

Collaborate and create

‘Learning in schools takes place within a social context’ (Stoll et al., 2002, p. 164). As such, we have collaboratively shaped our PLC. A recent staff survey identified ‘collaborating with colleagues’ and ‘dedicated time for professional learning’ as top requirements for effective professional learning. Such collaboration is essential for sustainable growth, creating coherence, allowing initiatives to ripple beyond their own silos and deepening collective capacity on campus and a sense of unity for a common objective.

To achieve this, leaders have relinquished power to genuinely distribute leadership. Expertise is valued irrespective of where it is found within the organisation. The skills, experience and knowledge that an individual or team brings to the table are valued more highly than the formal position that they hold. Fullan (2017) urges us to consider how to ‘liberate or give freedom to those immediately below you in the organization’ (p. 59). Applying this principle on the ground has been a priority, and leaders with more formal roles have removed barriers and avoided micromanagement, giving colleagues freedom to work together, advancing their own learning and that of the school. They are invited to authentically sit alongside their teams to collaborate and understand perspectives. During this process, leaders are mindful that trust could be lost if there is evidence of reverting to alternative hierarchical ways of working. We have witnessed that a genuine wish to work in this way is essential to success.

Inquire and investigate

To maximise staff-led inquiry, BSB replaced traditional top-down appraisal systems with autonomous professional learning (APL), a trust-based personal-choice model. Staff create their learning goals from five pathways, broadly or specifically connected to our school priorities.

Many of our professional learning initiatives follow a spiral of inquiry (Timperley et al., 2014) model, holding students’ learning needs at the core. Coaching ensures ample time for project review, fostering connections and transforming ideas into sustainable initiatives. This phase of leadership learning is critical, especially for staff members who have not previously led whole-school projects.

Working with trusted, external critical friends during this phase has allowed for connectivity beyond the school walls, bringing new thinking and expertise to professional learning inquiry.

APL emphasises that peer-accountability does not equate to a loss of control; rather, it shares control with those best positioned to make a difference: the staff themselves. The distinction between performance management and professional learning is maintained, with formal accountability structures employed as needed.

A recent staff survey indicated that 98 per cent of staff felt genuinely trusted to identify their own APL goal and complete their inquiry at an independent pace.

Reflect and review

Peer coaching supports the reflection process at all levels of the organisation. BSB leaders encourage risk-taking and innovative approaches, understanding that trust is essential for staff to take the leap required to stretch their learning and test the boundaries of their own creativity. Eight years in, staff feel open to reflect and review, considering setbacks as learning opportunities, fostering a culture of continuous improvement.

During this review phase, staff from all roles and functions are invited to share and sense-test their learning experiences with other staff, leaders and governors. Opportunities to present to wider groups provide feedback to refine and enable successful initiatives to be adopted into school policy and procedure.

Promote and prioritise

Brown and Flood (2019) demonstrate that ‘prioritising’ ensures the availability of essential resources for success. At BSB, dedicated leadership and governance groups ensure that professional learning priorities have the necessary resources. Our professional learning stewardship group creates a door for PLC inquiry findings to reach wider leadership fora.

Instrumental in prioritising connectivity and capacity has been the creation of professional learning partner (PLP) roles. PLPs are staff from any role or function at BSB who apply to lead aspects of the PLC. Their multifaceted role includes inquiry, leading communities and embodying the PLC culture. PLPs are given time and have direct access to policymakers in the organisation. From the outset, PLPs have been agents of change, promoting the growth and development of the PLC. There is clear evidence of their impact, including a significant reduction in silo practice and the promotion of unity and depth to professional relationships. Recent staff feedback shows that 99 per cent of staff considered the staff-led sessions to be effective in sharing skill and expertise, challenging thinking and purposeful collaboration, with 100 per cent considering that they added depth to curriculum review and inquiry.

Support and sustain

As much as we value the importance of the spontaneous and non-hierarchically led aspects of the PLC, we recognise that leaders play a crucial role, drawing parallels with the research of Brown and Flood (2019), in creating supportive structures and conditions for growth through processes, policies, leadership and mindsets. Key elements include fostering staff agency, creating open access to leaders and promoting autonomy of professional learning and innovation. Recent staff feedback shows that 99 per cent of staff considered that they had a high level of autonomy, choice and agency across our professional learning days’ learning opportunities.

Professional learning priorities feed into and grow out of our school development plan in a symbiotic way, with some examples being high-quality teaching and learning; a creative, dynamic and holistic curriculum, enhancing learning through cutting-edge technologies; and leading excellence and innovation in professional practice and development. Such integration ensures resources and support for initiatives and fosters coherence.

Conclusion

Eight years into the PLC journey, our qualitative and quantitative data, collected regularly through in -house and independent surveying and conferencing, shows high levels of staff satisfaction, parental support, high-quality practice, excellent recruitment and retention rates, and outstanding student outcomes. The emphasis on distributing leadership and developing leaders has been integral to this success. Notably, feedback from leaders has highlighted the importance of developing others and allowing for distributed leadership.

It is hoped that the findings of this case study offer supporting evidence to fellow Chartered College of Teaching professionals as we collectively continue to define and understand the value of teacher professionalism. We have offered evidence of a sophisticated ecosystem, rendered sustainable by deliberate leadership actions and ways of working. ‘Being open to change but not exploitable by fashion’ (Hargreaves and Fullan, 2012, p. 67) has been crucial. Over the last eight years, BSB has focused on developing expertise, emphasising deeper learning and connectivity and a sense of professionalism. The impact of this culture is demonstrative and transformative.

- Brown C and Flood J (2019) The three roles of school leaders in maximizing the impact of professional learning networks: A case study from England. International Journal of Educational Research 99: 101516.

- Fullan M (2011) The Six Secrets of Change: What the Best Leaders Do to Help Their Organizations Survive and Thrive. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Fullan M (2017) Indelible Leadership: Always Leave Them Learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

- Hargreaves A (1994) Changing Teachers, Changing Times: Teachers’ Work and Culture in the Postmodern Age. London: Cassell.

- Hargreaves A and Fullan M (2012) Professional Capital: Transforming Teaching in Every School. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Harris A, Jones M and Huffman JB (eds.) (2018) Teachers Leading Educational Reform: The Power of Professional Learning Communities. Routledge: Abingdon and New York.

- Kools M and Stoll L (2016) What makes a school a learning organisation? OECD Education Working Papers, no. 137. Available at: www.oecd.org/en/publications/what-makes-a-school-a-learning-organisation_5jlwm62b3bvh-en.html (accessed 23 January 2025).

- Müller LM and Cook V (2024) Revisiting the notion of teacher professionalism: A working paper. Chartered College of Teaching. Available at: https://chartered.college/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Professionalism-report_2-May.pdf (accessed 19 November 2024).

- Rosenholtz SJ (1989) Teachers’ Workplace: The Social Organization of Schools. New York: Longman.

- Stoll L and Fink D (1989) Changing Our Schools. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Stoll L, Fink D and Earl L (2002) It’s About Learning (and it’s About Time): What’s in it for Schools? Abingdon: Routledge.

- Timperley H, Kaser L and Halbert J (2014) A framework for transforming learning in schools: Innovation and the spiral of inquiry. Available at: www.educationalleaders.govt.nz/Pedagogy-and-assessment/Evidence-based-leadership/The-spiral-of-inquiry (accessed 19 November 2024).