Embedding a new approach to marking and feedback: Opportunities, challenges and lessons learned

SARAH CUNLIFFE, LEON WALKER AND REBECCA MORRIS, UNIVERSITY OF WARWICK, UK

Do I really know enough about the understanding of my pupils to be able to help each of them?

It was the summer of 2015 and we (Sarah and Leon) had just read this excerpt from Inside the Black Box (Black and Wiliam, 1998, p. 144). Our answer was definitely ‘NO’ and we wanted this to change. We were also drowning in hours of unproductive marking that had become a serious workload issue for our staff.

This is our story of how our feedback and workload problem ended up as one of the largest randomised controlled trials into feedback and marking in the UK – FLASH Marking (Morris et al., 2022).

What’s in the black box?

Saying no to that simple question wasn’t an easy thing to deal with. Feelings of failure quickly rose to the surface when we admitted that our students weren’t getting the help that they needed from us. Every teacher has high aspirations for their students; however, none of us knew what we needed to do next, so we decided to deepen our understanding of feedback and turned to research for help.

With little research experience, we struggled to navigate the complexity of what was available. Unlike now, there wasn’t the wealth of guidance reports offered by the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), so hours were spent reading documents that could cure even the worst case of insomnia! Our feelings of frustration and incompetence dissipated when we stumbled across 15 pages of clarity that changed everything.

Our eureka moment came in the form of a small pamphlet published in 1999 entitled Assessment for LearningKnown as AfL for short, and also known as formative assessment, this is the process of gathering evidence through assessment to inform and support next steps for a students’ teaching and learning: Beyond the Black Box (Broadfoot et al., 1999). This document gave us the opportunity to ‘see’ assessment in a completely different way. One phrase resonated with us – ‘assessment that promotes learning’ (p. 6). That was what we needed for our students, and it gave seven clear recommendations for achieving our goal of assessment that promotes learning:

- ‘it is embedded in a view of teaching and learning of which it is an essential part;

- it involves sharing learning goals with pupils;

- it aims to help pupils to know and to recognise the standards they are aiming for;

- it involves pupils in self-assessment;

- it provides feedback which leads to pupils recognising their next steps and how to take them;

- it is underpinned by confidence that every student can improve;

- it involves both teacher and pupils reviewing and reflecting on assessment data.’ (Broadfoot et al., 1999, p. 7)

These recommendations became our building blocks for FLASH.

History repeating

We were shocked when the research also explained why our current feedback and marking approach wasn’t working. For decades, researchers had been telling us what the issues were – we just weren’t listening. This excerpt from Black and Wiliam’s Inside the Black Box encapsulated what the research was saying.

High-stakes external tests always dominate teaching and assessment. However, they give teachers poor models for formative assessment because of their limited function of providing overall summaries of achievement rather than helpful diagnosis.

1998, p. 142

No grades!

The way in which we were teaching was fixated on the end point of external GCSE exams. We had to stop external tests from dominating our teaching and assessments; we needed to tell our teachers – NO GRADES!

This approach forced us to think differently about the purpose of our curriculum and assessments. The curriculum would no longer be preoccupied with the final exam and assessments predicting end grades. It would instead focus on the individual skills needed to be successful in the subject.

The content of our curriculum and assessments wasn’t the main issue; it was the learning goals that we were sharing with pupils. Every lesson was tweaked to include a specific skill as its learning goal. Within each lesson, these skills would be explicitly modelled so that students could clearly see what success looked like.

This explicit modelling of individual skills helped our students to recognise the standards for which they were aiming. Feedback in each lesson suddenly changed, as it now had a clearer focus. Students could self-assess their work by comparing the individual skill against what we had previously modelled to them. Self-assessment gave them the confidence to see their next steps and how to take them.

All of our feedback used the same approach, whether it was teacher’s feedback, self-assessment or peer-assessment. This created a shared language of assessment, and students started seeing all types of feedback as equally important to their development.

Later lessons allowed teachers to build up the complexity by combining these explicit skills. The schemes of work now had skill progression as the focus. Our end-of-topic assessments didn’t have to change, but the way in which we were assessing did. Rather than marking every piece of work like a GCSE question, we assessed it against the skills that we had explicitly taught and modelled, giving suggestions for improvement and development where needed, rather than a grade.

Beware of sharks

Around this time, workload issues and ineffective feedback and marking approaches were problems experienced by teachers across the country. Our strategy was used by the EEF as case study in ‘A marked improvement’ (Elliott et al., 2016), and they later decided to test our FLASH Marking idea through a national trial.

An independent evaluation team was appointed to scrutinise the efficacy of the FLASH approach. Our initial fears about what this entailed were quickly allayed and the team became instrumental in helping us to understand what success would look like.

We had no illusions that a national trial, including 103 secondary schools, over 900 teachers and 18,500 students across the country, was way beyond our classroom experience. We were asking schools and teachers to implement FLASH with a GCSE cohort and to change their teaching practices for the next two years. The line from Jaws resonated with us and was pinned up in the office as a daily reminder: ‘We’re gonna need a bigger boat!’

We decided that FLASH had to be delivered in a completely different way to our experiences of initiatives from the past. We had endured previous approaches that were dictated to us, without developing meaningful pedagogical knowledge and skills. Our approach needed to do something different.

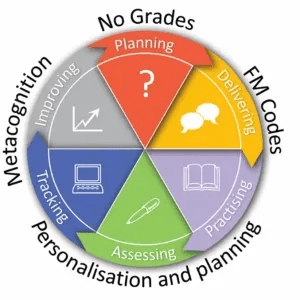

The trial’s aim of reducing workload meant that FLASH had to be straightforward for schools to implement. This non-negotiable aspect, coupled with our desire to develop pedagogical knowledge, shaped our training resources. We decided to amalgamate all of our underpinning theory and research plus the non-negotiable aspects of FLASH into one simple visual tool. This, we hoped, would help teachers to understand the process of feedback and how to integrate it into their lessons. We called it the FLASH cycle.

The FLASH cycle

Figure 1: The FLASH cycle

The FLASH cycle (see Figure 1) was nothing revolutionary; it was just what we considered to be ‘good’ teaching. It did, however, allow us to clearly explain to teachers how each of these elements of current practice needed to be slightly adjusted.

The questions that we asked our schools to consider were:

Planning: How to design a series of lesson that have specific skills as their learning focus

- What is the focus of the series of lessons?

- What explicit skills are relevant to the focus?

- How will you break down these skills in a series of lessons?

- Are your current assessments able to test these individual skills effectively?

Delivering: How to show your students exactly what they are aiming for

- How will you model the key skills to your students?

- How will you use model answers/other teaching aids to show effective/ineffective use of these skills?

Practising: How your students can rehearse these modelled skills and check their understanding with peer- and self-assessment

- Does each lesson have the opportunity for students to practise what they are learning?

- How can peer- and self-assessment be used effectively to develop metacognitive skills?

Assessing: How your students can demonstrate their best work by combining several skills that you have explicitly taught

- Can students independently demonstrate the range of skills that they have been explicitly taught?

Tracking and improving: How you can record your students’ responses and then give them targeted feedback to improve in future lessons

- How often does your department want to capture data from assessment?

- Based on your assessment, what skills should the student target to improve?

- How will these gaps be addressed?

The evaluation

The evaluation of the trial found that schools using ‘FLASH Marking reported a greater reduction in both total hours spent working and hours spent marking’ than schools in the control group (Morris et al., 2022, p. 4). Unfortunately, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the cancellation of externally assessed GCSEs in 2020 and 2021, the primary outcome data for the evaluation (GCSE attainment) was not collected. This was obviously a very disappointing situation and means that we must be very cautious in our claims about the impact of FLASH Marking on students’ progress or attainment. Despite this, the findings around teacher workload and the in-depth process evaluation indicate a potentially promising approach, and one that is firmly rooted in evidence-informed principles around assessment, feedback and professional development.

Staff and students involved in the trial were generally very positive about their experiences of FLASH and of the project. Teachers were pleased with the quality of training and the support available from the delivery team. Many heads of department and teachers also saw real value in the flexible approach to using and embedding FLASH Marking within the specific contexts of their schools, and perceived that the approach was having a positive impact on their students’ progress – as illustrated by the excerpts from our interviews with them below:

Our students across key stages now take ownership of their own work and improvement processes. We are increasingly finding students are not only able to identify their own strengths and weaknesses, but are able to accurately band/mark their own work against GCSE mark schemesCriteria used for assessing pieces of work in relation to particular grades. This was beyond our dreams previously.

Morris et al., 2022, pp. 34–35

We are now in the Final Countdown of this trial… and we’ve come a long way. We are all committed converts to this approach, as it has made us rethink our pedagogical practice, the structure of lessons, and the quantity and quality of teacher feedback. So much so, that we have rolled FLASH out to the current year 10s, and following the completion of this project, are planning to implement this in KS3 [Key Stage 3] too.

Morris et al., 2022, p. 46

We didn’t start the trial thinking that we had all the answers, and by the end we knew that we didn’t. FLASH became something that we could never have achieved on our own, and we learnt as much as those taking part.

So, if our article has inspired you to develop your own feedback approach, then the key points that we learnt along the way are:

- Be explicit about what success will look like. Describe what your teachers and students should and will be doing differently.

- Don’t try to bolt a new approach onto what you are currently doing. Feedback must be integrated into every aspect of your lessons and your curriculum planning.

- Any change will require a significant commitment of time. Use this to develop your colleagues’ understanding of core principles and to build a productive and safe culture of professional dialogue. This will ensure that they know why and how their current practice should change and how they can monitor and develop their own practice.

- And if you really want to figure out whether what you’ve introduced is effective, consider how you can robustly evaluate the approach. Evaluations are really challenging, but our work with the FLASH evaluators was instrumental for understanding what we were trying to achieve and for constant development and improvement of the FLASH approach. Being part of a large EEF trial won’t be possible for everyone – but there are lots of helpful resources and researchers out there who are able to support.

What we learnt most from the trial is that if you gather a group of committed professionals together from across the country and support them to deliver an evidence-informed approach for developing their own practice and improving students’ outcomes, then you’ll be astounded at what can be achieved.

It was a privilege that we will never forget.

- Black P and Wiliam D (1998) Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. Phi Delta Kappan 80(2): 144–148.

- Broadfoot P, Daugherty R, Gardner J et al. (1999) Assessment for learning: Beyond the black box. Assessment Reform Group. Available at: www.researchgate.net/publication/271848977_Assessment_for_Learning_beyond_the_black_box (accessed 19 March 2024).

- Elliott V, Baird JA, Hopfenbeck TN et al. (2016) A marked improvement? A review of the evidence on written marking. Education Endowment Foundation. Available at: https://d2tic4wvo1iusb.cloudfront.net/production/documents/guidance/EEF_Marking_Review_April_2016.pdf?v=1705853286 (accessed 19 March 2024).

- Morris R, Gorard S, See BH et al. (2022) FLASH Marking: Evaluation report. Education Endowment Foundation. Available at: https://d2tic4wvo1iusb.cloudfront.net/production/documents/projects/Flash-Marking-final.pdf?v=1705856009 (accessed 19 March 2024).