Feedback is not a gift

MARCO NARAJOS, DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION, UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD, UK

Rationale

Research has long indicated that feedback supports attainment (Hattie and Timperley, 2007). This has led to assessment by regular or deep marking becoming a significant source of burdensome workload, which significantly correlates with poor teacher wellbeing (Brady, 2020; Jerrim and Sims, 2020). Teaching at an independent senior school, I argued that these practices placed too strong an emphasis on teacher-led assessment and ignored learners’ roles in developing substantive knowledge and self-regulated learning (SRL) through their engagement in assessment and feedback. In the context of a department policy of fortnightly individual written feedback for all pupils, I developed and investigated a new and more efficient approach to feedback that emphasised learners’ agency and engagement.

Study design

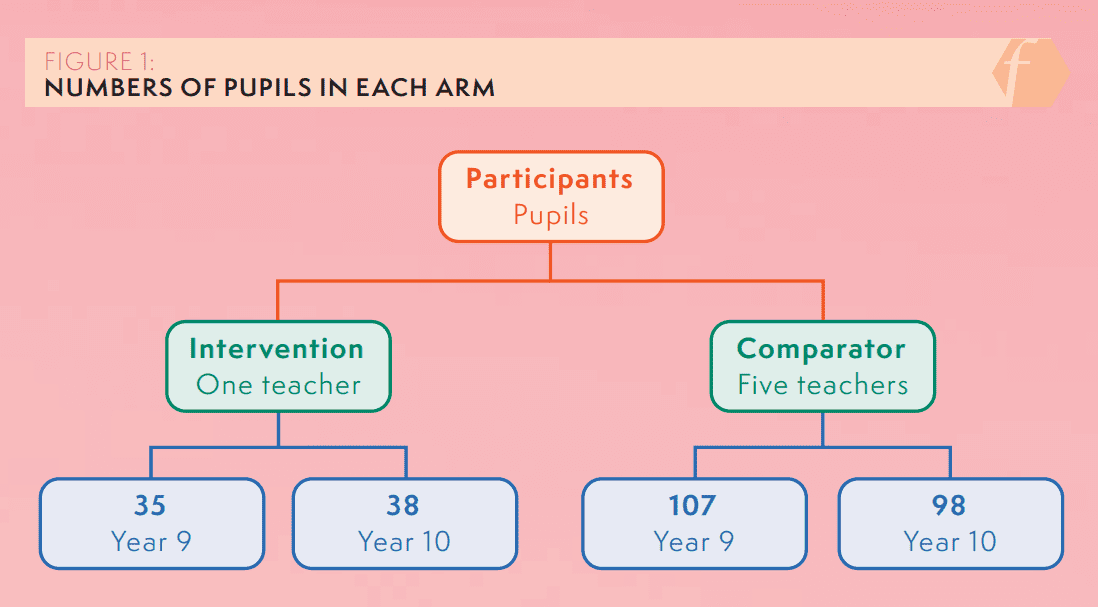

After gaining ethical approval and permission from the headteacher, 15 classes of Year 9 and 10 learners of IGCSE biology were assigned to one of two arms in a quasi-experimental study (Figure 1). The four classes I taught formed the intervention group and the remaining 11 classes became the comparator group, which received usual assessment and feedback practices over the 10-week intervention period.

Figure 1: Numbers of pupils in each arm

I developed an intervention that consisted of giving whole-class feedback to learners after each instance of bookmarking once every fortnight. Lesson observations and discussions with colleagues were formative in iteratively modifying the intervention. The intervention used principles discussed in the literature (Hattie and Wollenschläger, 2014; Winstone et al., 2017; Jonsson and Panadero, 2018).

- Feedback is targeted at the process and self-regulation levels, with minimal task-level corrective feedback

- Feedback provides relevant success criteria or model answers for pupils to evaluate their work against

- The teacher engages in dialogue with selected pupils to demonstrate to the whole class how success criteria can be achieved

- The teacher explicitly models metacognitive processes

- The teacher highlights salient strategies and areas of success and development, identifying specific learning actions for pupils to choose from.

Baseline results

This article reports on learners’ perceptions of the feedback given in biology lessons before and during the intervention period. At baseline, prior to the intervention, a representative sample of 251 pupils responded, endorsing that they regularly received and used both individual and whole-class feedback. Most said that both approaches told them how to improve. However, just under half (49 per cent) of pupils carefully read and responded to written feedback, compared to 64 per cent for whole-class feedback.

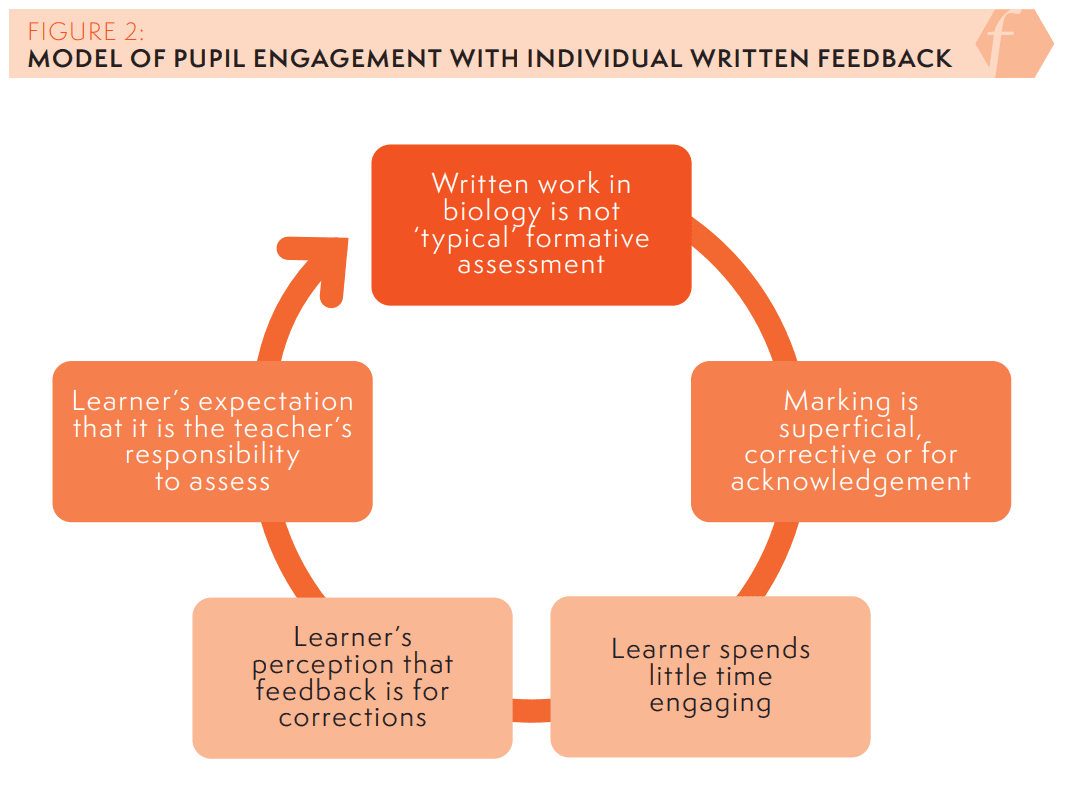

Following a reflexive thematic analysis of interview transcripts, I identified three themes in pupils’ perceptions at baseline. Firstly, they saw themselves as the recipients of the assessment process, which was seen as providing accurate evaluations of their progress. This was expressed as expectations of teachers marking homework, notes and classwork, alongside tests. Pupils also recognised spoken feedback and described valuing this approach if a teacher assessed their work. Unlike the teachers I interviewed, the pupils believed simple praise and getting merits to be forms of teacher feedback, and they believed these to reflect the quality of their work. Feedback was only seen as the end of an assessment process, rather than the start of a learning one. This could be because the homework that we give tends to be based on retrieval practice. Whereas typical formative assessment involves learners editing a piece of ongoing work, teacher feedback in biology involves what corrections should be made to completed work, rather than focusing on how the learner improves for the future.

Secondly, pupils saw assessment and feedback as carrots and sticks for learning. They used teacher-led assessment and feedback nearly exclusively to decide on the focus and effort needed for revision, indicating poor SRL. They depended on marking to bolster their notes. Some used marking to avoid metacognitive thinking on their areas for improvement: ‘If you’re really struggling with something, you don’t want to say it verbally, [the teacher] can know [from marking your book].’ This could be explained by individual feedback practices not allowing pupil engagement with self-assessment (Elliott et al., 2020; Muijs and Bokhove, 2020).

Finally, learners perceived individual feedback to be inherently more useful compared to whole-class feedback, even when they rated the quality of whole-class feedback as higher than individual feedback in the questionnaire. Perceived utility of the feedback approach is independent of its perceived quality. Good feedback is something that the teacher gives to a learner, like a gift following assessment (Askew and Lodge, 2004). These three themes were used to create a model of pupil engagement with individual written feedback (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Model of pupil engagement with individual written feedback

Post-intervention results

Despite both groups having similar perceptions at baseline, intervention pupils reported improvements in their perceptions of both individual and whole-class feedback. Unexpectedly, the intervention pupils reported greater attentiveness, satisfaction and sense of usefulness towards individual feedback compared to the comparator group. They also reported more regular whole-class feedback, but without changes to attentiveness, quality, utility or satisfaction with whole-class feedback.

In interviews, a minority felt that whole-class feedback was irrelevant if it did not provide them directly with information about their own performance. This highlights the importance of making the purpose of feedback explicit to all learners. Conversely, when learners felt that they had to engage with the whole-class feedback directly, they self-assessed more and were more likely to perceive the feedback as applicable. This suggests that learners’ use of this form of feedback requires the development of SRL and explicit guidance to form routines that enable self-assessment (Andrade, 2018). These findings are summarised in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Model of pupil perceptions of the intervention

Implications

In this quasi-experimental study, using a psychometric questionnaire that measures aspects of SRL, I found evidence of small improvements in the intervention group in effort regulation and intrinsic motivation, accompanied by increased pupil progress compared to the comparator group. It was impossible to establish causality between the whole-class feedback intervention and changes to attainment and SRL. However, it is possible to conclude that the intervention did not detriment their learning outcomes, which is significant, given that it reduces workload significantly, with potential benefits for teacher workload and wellbeing.

Given the need for further investigation and implementation evaluation, the study should stimulate the following questions for discussion.

-

- What does your assessment and feedback policy claim is the purpose of assessment and feedback in teaching and learning?

- What do your pupils think is the purpose of assessment and feedback?

- How do your learners engage with feedback and use it in and out of the classroom?

- How can your assessment and feedback practices become more efficient for teachers and more actively engaging for learners?

- How do your assessment and feedback practices influence your learners’ self-regulation of learning?

References

- Andrade HL (2018) Feedback in the context of self-assessment. In: Lipnevich AA and Smith JK (eds) The Cambridge Handbook of Instructional Feedback. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 376–408.

- Askew S and Lodge C (2004) Gifts, ping-pong and loops – linking feedback and learning. In: Askew S (ed) Feedback for Learning. London: Routledge, pp. 1–18.

- Brady J (2020) Workload, accountability and stress: A comparative study of teachers’ working conditions in state and private schools in England. PhD Thesis, University of Cambridge, UK.

- Elliott V, Randhawa A, Ingram J et al. (2020) Feedback in action: A review of practice in English schools. Education Endowment Foundation. Available at: https://d2tic4wvo1iusb.cloudfront.net/production/documents/guidance/EEF_Feedback_Practice_Review.pdf?v=1711133095 (accessed 23 March 2024).

- Hattie J and Timperley H (2007) The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research 77(1): 81–112.

- Hattie J and Wollenschläger M (2014) A conceptualization of feedback. In: Ditton H and Muller A (eds) Feedback und Rückmeldungen. Munster: Waxmann Verlag GmbH, pp.135–149.

- Jerrim J and Sims S (2020) Teacher workload and well-being: New international evidence from the OECD TALIS study. Available at: https://johnjerrim.files.wordpress.com/2020/11/working_paper_workload_wellbeing_november_2020.pdf (accessed 23 March 2024).

- Jonsson A and Panadero E (2018) Facilitating students’ active engagement with feedback. In: Lipnevich AA and Smith JK (eds) The Cambridge Handbook of Instructional Feedback. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 531–553.

- Muijs D and Bokhove C (2020) Metacognition and self-regulation: Evidence review. Education Endowment Foundation. Available at: https://d2tic4wvo1iusb.cloudfront.net/documents/guidance/Metacognition_and_self-regulation_review.pdf?v=1642679296 (accessed 23 March 2024).

- Winstone NE, Nash RA, Parker M et al. (2017) Supporting learners’ agentic engagement with feedback: A systematic review and a taxonomy of recipience processes. Educational Psychologist 52(1): 17–37.