Leading quality use of research in schools

JOANNE GLEESON, MARK RICKINSON, LUCAS WALSH AND BLAKE CUTLER, FACULTY OF EDUCATION, MONASH UNIVERSITY, AUSTRALIA

Introduction

Internationally, educators and education systems are becoming increasingly aware that using research can improve their work (e.g. OECD, 2022). Previous studies provide powerful reasons for educators to use research, showing links to better teaching skills and improved and more equitable student learning outcomes (e.g. Malin and Brown, 2022; Mincu, 2015). However, using research well and incorporating it into practice is complex and demanding work, with educators requiring support to do this (Rickinson et al., 2024). Key to building schools’ capacities to use research are certain leadership practices that, when employed, have real potential to impact educational practice positively.

Drawing on the work of the Monash Q Project in Australia, this brief article aims to explore what leading quality use of research in schools involves. It does so first by unpacking the idea of quality use of research (or using research well), and then by outlining what is involved in the key leadership practices of modelling, involving and supporting. Using a case study of one Australian school that demonstrates these practices well, the article acts as a developmental resource for all educators by putting forward considerations about the ways in which they can improve their own research-use leadership capacities.

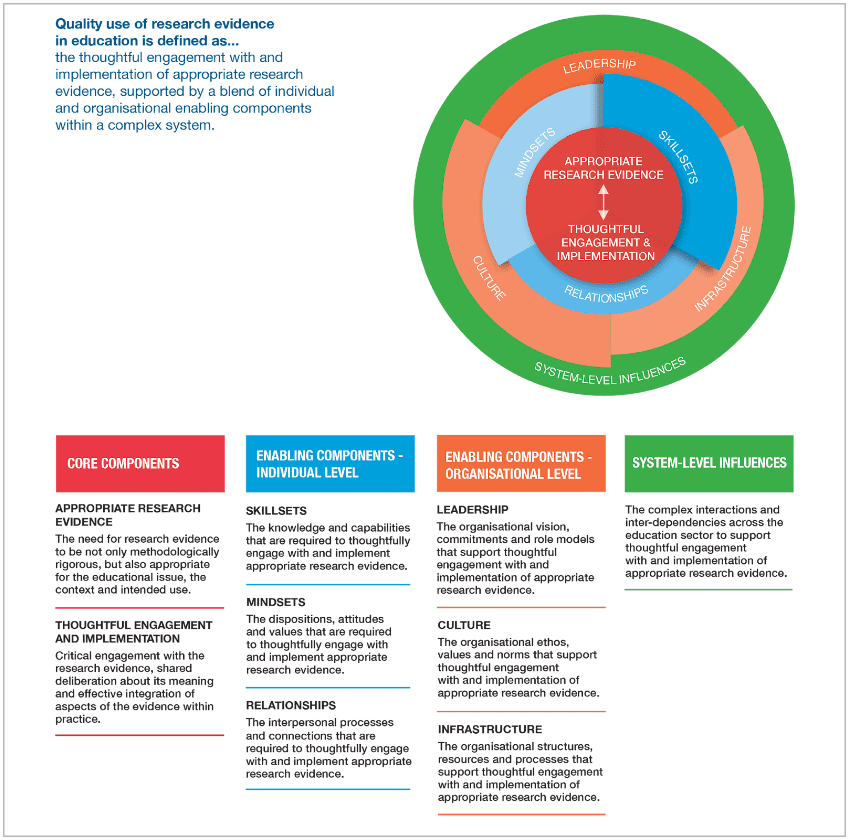

The Monash Q Project

The Monash Q Project has involved close collaboration with over 2,100 educators and 200 education system leaders to understand and improve the use of research in Australian schools (Rickinson et al., 2024). The early phase of the project involved a systematic cross-sector review and narrative synthesis of 112 relevant publications. The aim of the review was to explore definitions and descriptions of quality evidence use in different sectors in order to inform the development of the Quality Use of Research Evidence (QURE) framework for education (Rickinson et al., 2020, 2022). As shown in Figure 1, quality use of research is defined as comprising two core components: appropriate research evidence, and thoughtful engagement and implementation. It is supported by three individual enabling components (skillsets, mindsets and relationships) and three organisational enabling components (leadership, culture and infrastructure), which are shaped by wider system-level influences.

Figure 1: Quality Use of Research Evidence (QURE) framework

This article focuses on the organisational enabler of leadership (see Figure 1). It draws on educators’ responses to our first survey (n=492), follow-up interviews (n=27 transcripts) and our third survey (n=414) to explore the quality research-use leadership practices shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Quality research-use leadership practices

| The practice involves: | |

| Modelling |

|

| Involving |

|

| Supporting |

|

Details about the design, conduct and analysis of research methods are outlined elsewhere (Rickinson et al., 2024), with all research materials available on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/v27fx).

Leadership practices for quality use of research

Modelling

In our work, educators were clear that they looked to leaders to demonstrate the value of research use, what using research well looked like on the ground and how they should go about incorporating research into their own work (67 per cent of interviews, 31 per cent of Survey 1 responses). Whether you are in a leadership role or not, you can role-model quality research use in two main ways.

Firstly, you can be a model research user yourself, using research in your everyday work and investing in developing your own research-use skills, mindset and relationships (see individual enabling components in Figure 1). Educators in our work described this as ‘walking the talk’ – making sure that your research-use attitudes and practices are visible to others, which sends important signals to colleagues that you are prepared to enact yourself what you are asking of them.

Secondly, role-modelling can involve you showing others how a research-informed practice ought to be implemented (75 per cent of Survey 3 responses). Educators described role-modelling taking place in varied group settings, including: professional learning sessions, both within and beyond the school; during classroom demonstrations and observations; team, leadership and/or faculty/subject domain meetings; school presentations; and research-based question–answer forums.

Involving

Using research well is highly relational, with educators in our work describing collaboration as a critical way of practising quality research use (81 per cent of interviews, 35 per cent of Survey 1 responses). You can involve others in research use in two main ways.

Firstly, if you are using research yourself, you can work collectively with others. Being mindful of the nature and complexity of the research-use task can help you to do this in effective ways. When we spoke with educators, tasks like finding research or checking its relevance seemed to need only light-touch, informal or networking-type relational processes. Trialling and implementing research, however, seemed to require more involved and structured consultation and collaboration.

Secondly, you can involve others by sharing research yourself and promoting the benefits of a knowledge-sharing school culture (81 per cent of Survey 3 responses). Through knowledge-sharing, colleagues may be encouraged to experiment with research and develop their research-use capacities. Educators described sharing ideas and knowledge from research in informal group settings, such as reading circles or networking forums, as well as more formal group settings, such as whole-school professional development days.

Supporting

When educators spoke about using research, they often emphasised that it was highly skilled work (89 per cent of interviews, 91 per cent of Survey 1 responses) that required various supports to be done well (81 per cent of interviews, 18 per cent of Survey 1 responses). There are two main types of support that can be provided to facilitate improved research use.

The first type is material support in the form of access to research (64 per cent of Survey 3 responses) and scheduled time during school hours to engage with it (72 per cent of Survey 3 responses). However, providing access and scheduling time can prove challenging, with educators in our work recommending to ‘start small’. For example, existing meetings and processes, such as annual performance reviews or strategic planning, can be leveraged to include time for research use. Additionally, access to and engagement with research may be improved by creating resource hubs, as online repositories and/or physical spaces, that house a range of research-informed materials.

Secondly, educators described wanting developmental opportunities to experiment with research use and improve their skills and confidence. These types of opportunities may comprise internal activities, such as reading and reflecting on research-use case studies or completing the QURE Assessment Tool (https://research.orima.com.au/QURE_AssessmentTool/Logon/logon.php?) and setting some improvement goals, or external experiences, such as participating in research-use professional learning courses or attending conferences. You can also provide support by leveraging or building certain developmental structures, such as professional learning communities, instructional leader models and coaching/mentoring programmes.

Overall, research use within your school can be improved if you build your research-use leadership capacities in modelling, involving and supporting. The following exemplar case study shows how these practices can come together in action.

Case study

This case study involves a team of senior leaders and teachers at a government secondary school located in the main city of a state in Australia. At the time, the English faculty were seeking to improve students’ writing and, in turn, their English assessment outcomes, by implementing a new research-informed teaching approach.

Modelling

Over several months prior to deciding on and designing the new teaching approach, the head of faculty and the deputy principal set aside scheduled time in their diaries each week to read and analyse multiple sources/types of research. From the outset, they associated research use with their ‘professional practice’ as teachers, and wanted to be role models of using research well to staff.

[Without research] we would not have known where to start – there would have been a lot more guesswork.

Head of faculty, interview

During later implementation stages, the head of faculty role-modelled the new approach in classrooms, with teachers observing. These demonstrations were followed by debrief sessions, where all faculty members discussed what worked during trials and what didn’t, and then brainstormed potential improvements.

Seeing those strategies… that had been fairly new to me being modelled by a leader in the school was a great way to see how effective they could be because they aided my learning… it actually helps me visualise what I’m going to be learning today.

Early career teacher, interview

Involving

From early on, senior faculty members were involved in reading research, and worked alongside the head of faculty to determine common research assessment criteria and build a shared understanding of research-informed strategies that would ‘fit’ their context.

Having another voice to balance off [was important] and also to realise that we’re thinking similar things. We also made a little synthesis table that we could see commonalities across [the strategies] as well and discount some of them pretty quickly.

Head of faculty, interview

Over time, the entire faculty was included in formal and informal collaborative sessions about the research-informed writing approach. These sessions included weekly team meetings where the research was discussed, and all teachers were given opportunities to present their interpretation of the research or how they had trialled it in their class.

[We are] often given meeting time to… integrate strategies into our programmes… and deconstruct and talk about the strategies that we’ll use together… giving everyone the opportunity in the faculty to demonstrate and share whether they’ve had success with those things.

Teacher, interview

A formal mentor programme, where more experienced teachers were paired with newer or less experienced teachers for additional support, was another way in which the faculty team collaborated.

Supporting

Finally, the head of faculty and the deputy principal established various infrastructures to support research use and sustain the research-informed change. This support included regular inquiry-based professional learning sessions, centred on research-use skill and knowledge development, and scheduled time for teaching teams to work collaboratively on the approach. Over a period of 18 months, alongside redistributing planning and administrative workloads to allow more time for research use, senior leaders also stopped other isolated or smaller change projects for this initiative to take priority.

[Leaders support the] kind of mindset that it’s okay to be developing and still learning how to implement research. That mindset is something that’s given me a lot more confidence to attempt to implement research. [Scheduled time to reflect] is a critical element in making sure that your practice is developing, to realise when you’ve done something wrong and work out how you can do it better.

Early career teacher, interview

Conclusion

Drawing on the work of the Monash Q Project, this brief article has described what is involved in three key quality research-use leadership practices. By using educators’ descriptions and experiences of what using research well looks like on the ground, the article has provided practical insights into the ways in which educators can build their research-use leadership capacities. To conclude, we encourage all educators, irrespective of their role, to consider what they could do to model, involve others in and support quality use of research in their schools.

- Malin JR and Brown C (2022) Introduction: What can be learned from international contexts about how to foster evidence-informed practice? In: Brown C and Malin JC (eds) Emerald Handbook of Evidence-Informed Practice in Education. Leeds: Emerald, pp. 1–13.

- Mincu ME (2015) Teacher quality and school improvement: What is the role of research? Oxford Review of Education 41(2): 253–269.

- OECD (2022) Who Cares About Using Education Research in Policy and Practice? Strengthening Research Engagement. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available at: www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/who-cares-about-using-education-research-in-policy-and-practice_d7ff793d-en (accessed 21 June 2024).

- Rickinson M, Cirkony C, Walsh L et al. (2022) A framework for understanding the quality of evidence use in education. Educational Research 64(2): 133–158.

- Rickinson M, Walsh L, Cirkony C et al. (2020) Quality Use of Research Evidence framework. Monash University. Available at: https://bridges.monash.edu/articles/report/Quality_Use_Of_Research_Evidence_QURE_Framework_Report/14071508 (accessed 21 June 2024).

- Rickinson M, Walsh L, Gleeson J et al. (2024) Understanding the Quality Use of Research Evidence in Education. Abingdon: Routledge.