Penryn Creativity Collaborative: Developing teaching for creativity in primary and secondary schools through an action research model

URSULA CRICKMAY, SCHOOL OF EDUCATION, UNIVERSITY OF EXETER, UK

SARAH CHILDS, PENRYN COLLEGE, UK

KERRY CHAPPELL, SCHOOL OF EDUCATION, UNIVERSITY OF EXETER, UK

Introduction

Creativity has frequently been identified as a core skill that is necessary for the workforce and future citizenship, given the context of ongoing uncertainty and change across interconnected social, political, environmental, technological and economic domains (OECD, 2018). While challenges to the notion of teaching ‘soft skills’ such as creativity have also been raised – not least that they are often dependent on domain-specific knowledge – there is nevertheless a recognition that developing and nurturing creativity is important. The urgency of this is particularly notable in Cornwall, an area that has historically struggled disproportionately due to rural isolation, coastal deprivation and societal inequality (Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Leadership Board, 2020). To respond to this need, schools in the Penryn Partnership, a group of eight primary schools and one secondary school in Cornwall, worked with local industry and cultural partners and the University of Exeter (UoE) School of Education to develop their practice in teaching for creativity, utilising an action research model. Together, they explored the different ways in which creative pedagogies manifested in the Penryn Partnership, and looked at how students’ creative skills were progressing over time.

Wider context for action research

The Penryn Partnership is part of Creativity Collaboratives, a national pilot programme of eight school clusters across England. The collaboratives are working together to test innovative practices in teaching for creativity, aiming to share and inspire teaching and learning for a future curriculum and system-wide change. The programme, launched in October 2021, is funded by Arts Council England with support from the Freelands Foundation, as a response to the Durham Commission on Creativity and Education (Arts Council England and Durham University, 2019). Penryn Creativity Collaborative (PCC) is the South West pilot programme, and has a specific focus on exploring how teaching for creativity across the curriculum leads to young people who are better prepared for their future in a changing workforce.

Developing a model of creative skills

Research suggests that teachers often find it hard to define creativity or to describe examples of their students using their creative skills. Lucas (2021, p. 7) explains:

Two challenges for schools seeking to embed creativity have historically been, firstly, that it is too abstract a concept… to be specific enough to develop and, secondly, that it is not clear how to integrate creativity into the formal and informal curriculum intentionally.

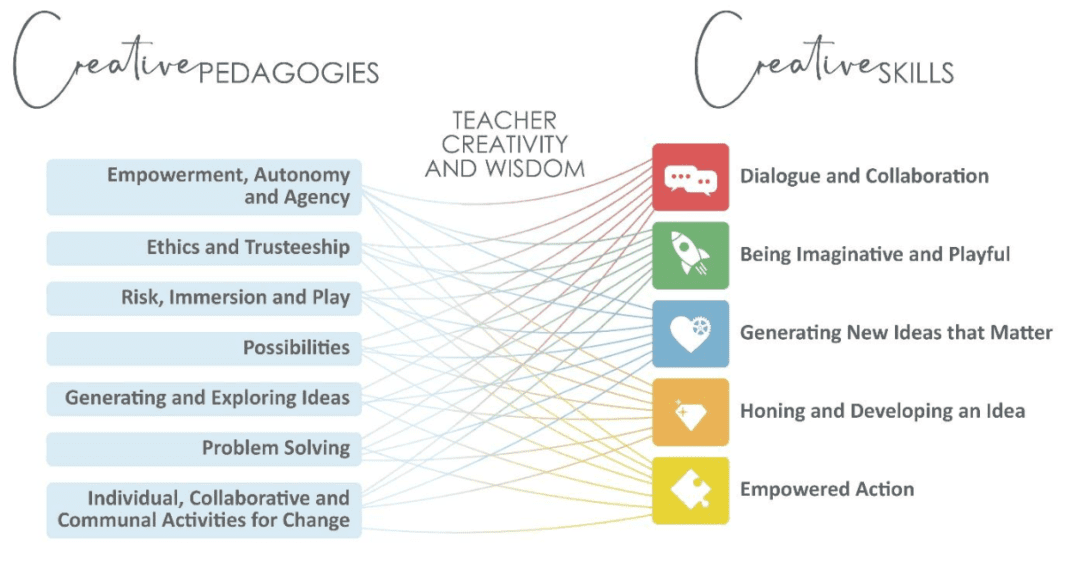

The first stage of our research was thus to establish a language of creative skills that was meaningful to the participating teachers and students. Beginning with a literature review (Crickmay et al., 2023a), we drew on wide-ranging understandings of creativity from research. We honed this through focus groups with students, teachers, and industry and cultural partners, developing a creative skills model that was specifically grounded in the needs and understandings of the PCC, with an emphasis on creativity for workforce readiness. In contrast to more individualised understandings of creativity, ours is a dialogic model, rooted in relational and collaborative approaches to imaginatively generating and developing new ideas, processes and products that matter. A consideration of ethical consequences and diverse values is woven through the definition (see Figure 1). We added a framework of creative pedagogies adapted from Cremin and Chappell’s (2019) systematic review of 30 years of empirical research on this topic.

Figure 1: PCC creative pedagogies and skills (Crickmay et al., 2023a)

The action research process

Next, we utilised a collaborative model of action research based on prior work by the Creativity Action Research Awards (Chappell, 2008). This model is grounded in university researchers researching ‘with’ rather than ‘on’ teachers, and empowering teachers to own both the research process and the creative skills and pedagogies. A lead action research teacher was identified by headteachers from each primary school, plus a small group of teachers who led in the secondary school, from Early Years to Key Stage 4. Working with the PCC lead, UoE researchers rigorously trained and mentored this team as action researchers, collaborating with industry and cultural partners through a process including:

- continuing professional development (CPD) days, where teachers were trained in key action research processes, from developing research questions through to collecting and analysing data and report-writing

- teachers’ own research questions being linked to the creative skills and pedagogies frameworks and addressing an area of development for their own classroom practice and often the school development plan

- some teachers implementing specially designed projects or lessons, while others focused on classroom practice as usual

- industry and cultural partners collaborating with teachers in diverse ways, providing CPD, visiting classrooms and hosting visits to cultural venues and industry workplaces

- teachers being mentored in small groups by the UoE team

- the PCC lead providing face-to-face teaching and learning visits, offering practical support through in-class observations and discussion with the teacher and each school headteacher

- action research teachers sharing the research and findings within their own schools and beyond.

Each teacher also published their own report findings, while an overarching data synthesis was conducted and published by the UoE team (Crickmay et al., 2023b).

Findings

Linked to their school development plans, each action research teacher worked within their existing school systems, either as coaches or creativity leads. Findings demonstrated the freedom that they had experienced during this process, alongside feeling energised and invigorated. Often, lessons used problem-solving approaches, addressed real-world problems and were transdisciplinary. Teachers reflected on how their students then felt more empowered in their learning, more motivated and engaged. Through a range of approaches to teaching for creativity, students were observed actively and ably engaging in dialogue and collaboration, especially question-posing and responding, along with strong examples of reflecting, analysing and evaluating.

For example, a primary action research project explored ‘How might collaborative “learning friends” empower children to take empowered action in their learning?’ (Fenton, 2023), developing approaches to child-led learning. This project saw Year 5 students trusted to lead sessions for Year 1 students without adult input. Nurturing the potential of teaching for creativity for social, emotional and mental health, ‘learning friends’ established new relationships, fostering opportunities for sharing and allowing time to play, problem-solve, take risks and, in turn, develop resilience.

An example secondary action research project asked the question ‘How can we harness creative skills when thinking like a scientist?’ (Van-Veen, 2023). Van-Veen observed creative skills being used to design and plan scientific investigations, with Key Stage 3 students developing ideas for their own investigations. ‘The students did not notice that they were thinking like a scientist during the activities until prompted to reflect. Some commented that it did not feel like science, more like STEAM or art even though what they were doing is exactly what scientists do.’ (p. 7)

As a result of the action research, teachers shared their perception that teaching for creativity not only enriches the classroom experience but also makes knowledge stickier, more memorable and easier to retrieve and recall when required. Students told us that they want more opportunities for dialogue and collaboration, alongside opportunities to lead their own learning.

After the first cycle of action research, the ambition of PCC has been to embed and grow the new practice. Teachers and headteachers are currently cascading learning from their research across their schools and wider networks, regionally and nationally. PCC also launched a toolkit (https://penryn-college.cornwall.sch.uk/creativity-collaboratives/toolkit), developed following the research. It includes examples of teaching for creativity across the curriculum and support for developing practice in others, and offers ideas that ‘you might like to try’ with young people from Key Stages 1–4. Fostering a coaching programme and ongoing CPD continues to enrich teachers’ and students’ learning.

Conclusion

PCC was built on a wealth of existing research on creative skills and pedagogies, which it brought together with a strong focus on teachers as reflective practitioners, appreciating their ‘art’ of teaching’ (Stenhouse, 1983). The collaborative action research process provided a model for developing and embedding this evidence-informed practice, as well as gathering data showing the impact on students’ creative skills. It has resulted in an array of different classroom practices across the curriculum that are bespoke to the individual schools and owned by the teachers involved.

- Arts Council England and Durham University (2019) Durham Commission on Creativity and Education. Available at: www.artscouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/download-file/Durham_Commission_on_Creativity_04112019_0.pdf (accessed 2 July 2024).

- Chappell K (2008) Mediating creativity and performativity policy tensions in dance education-based action research partnerships: Insights from a mentor’s self-study. Thinking Skills and Creativity 3(2): 94–103.

- Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Leadership Board (2020) The Cornwall Plan 2020–2050. Available at: https://letstalk.cornwall.gov.uk/cornwall-plan (accessed 2 July 2024).

- Cremin T and Chappell K (2019) Creative pedagogies: A systematic review. Research Papers in Education 36(3): 299–331.

- Crickmay U, Childs S and Chappell K (2023a) Preparing for a creative future: Year one report: Question, challenge & explore. Available at: https://home.penryn-college.cornwall.sch.uk/cc/Penryn%20CC%20Year%201%20Report.pdf (accessed 2 July 2024).

- Crickmay U, Childs, S and Chappell K (2023b) Preparing for a creative future: Year two report: Build and test. Available at: https://penryn-college.cornwall.sch.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Penryn-CC-Year-2-Report.pdf (accessed 2 July 2024).

- Fenton J (2023) How might collaborative ‘learning friends’ empower children to take empowered action in their learning? Available at: https://penryn-college.cornwall.sch.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/PCC-AR-REPORT-Fenton-2023.pdf (accessed 2 July 2024).

- Lucas B (2021) Creative school leadership. Available at: https://assets.website-files.com/5f5ebe0e64fb4656fd0351cb/60472711850f9a270f50bae8_Leading%20for%20Creativity_Bill%20Lucas.pdf (accessed 2 July 2024).

- OECD (2018) The future of education and skills: Education 2030. Available at: https://repository.canterbury.ac.uk/download/96f6c3f39ae6dcffa26e72cefe47684172da0c93db0a63d78668406e4f478ae8/3102592/E2030%20Position%20Paper%20%2805.04.2018%29.pdf (accessed 2 July 2024).

- Stenhouse L (1983) Authority, Education and Emancipation: A Collection of Papers. Oxford: Heinemann Education.

- Van-Veen E (2023) How can we harness creative skills when thinking like a scientist? Available at: https://penryn-college.cornwall.sch.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/PCC-AR-REPORT-Van-Veen-2023.pdf (accessed 2 July 2024).