Talking transitions: Harnessing the power of oracy to support vocabulary acquisition during the primary to secondary transition

Kathleen McBride, Learning Design Lead, Voice 21, UK

Introduction

During the transition from primary to secondary school, there is a significant increase in the quantity and complexity of vocabulary that students encounter at school (Deignan et al., 2022). This is also a time of social and emotional upheaval, as they learn to navigate unfamiliar environments and adjust to new routines (Harris and Nowland, 2021) – a time when students’ confidence in their academic abilities and perceptions of self can shift. A high-quality oracy education has the capacity to support transitions (De Vries and Rentfrow, 2016), improving both academic (EEF, 2021) and wellbeing outcomes, particularly for students from lower socio-economic status backgrounds (Oracy APPG, 2021).

Championing oracy for vocabulary development

Oracy-rich classrooms place talk at the forefront of teaching and learning, providing students with opportunities to hear and use new vocabulary in context. Deignan et al. (2022) write that as students move from primary to secondary, the language of school moves further away from the language of home, and students face a linguistic transition too. Everyday speech is inherently less likely to contain the academic vocabulary that students need to access the curriculum as they move from one key stage to another (Quigley, 2019). However, research suggests that purposeful, structured and progressive talk leads to learning gains (Howe et al., 2019).

While reading and writing may seem to be the most effective ways of introducing and assessing students’ mastery of new language as they move through key stages, there is a risk that a preference for written modes exacerbates differences in students’ academic language levels (Gascoigne and Gross, 2017). Vocabulary size can become a barrier to comprehending written text, and oracy has an important role to play in creating equity of access to the curriculum. We know that oral language is a powerful vehicle for learning new words (Beck et al., 2013) – it is, of course, how early language is acquired – and is one that teachers can be supported to use effectively to build students’ vocabulary as they move beyond primary school.

The Voicing Vocabulary project

To deepen our understanding of the relationship between oracy and vocabulary at transition, we designed a two-year project: Voicing Vocabulary.

The aims of the project were to:

- improve the vocabulary of Key Stage 2 and 3 students in participating schools

- establish an oracy-rich, cross-phase approach to vocabulary development.

We recruited 12 schools (three secondary schools and their neighbouring primaries) across three regions of England who would work together on a series of in-person and online development days to establish shared approaches to oracy and vocabulary teaching. To evaluate the impact of the project, we utilised a range of quantitative (the New Group Reading Test and teacher and student surveys) and qualitative measures (teacher interviews, teacher and student focus groups and teacher questionnaires).

Establishing a shared understanding of oracy

We cannot assume that students automatically know how to engage effectively in classroom talk (Mercer and Hodgkinson, 2008) and, as with any other skillset, attention to what, how and when students acquire oracy skills is key to creating the conditions where talk can become an effective vehicle for vocabulary learning. To support this, we introduced teachers to the Oracy Teacher Benchmarks (Voice 21, 2019) and the Oracy Framework (Mercer et al., 2017), connecting these principles to practical strategies such as discussion guidelines, sentence stems and different roles for talk.

Knowing which words to teach

During the project, we explored the tiered approach (Beck et al., 1987) to categorising vocabulary to support teachers’ decision-making around vocabulary selection. Tier 1 words – those most likely to be learned through everyday experiences – are also those most connected to the language of informal speech, thus requiring less explicit instruction. Tier 2 and 3 vocabulary is the language that we are most likely to encounter in written text – language that we associate with academic discourse and specialised knowledge (Nation, 2001). Deciding which words are likely to be most useful for students across the curriculum is difficult to do in isolation and is an aspect of curriculum planning that benefits from a collaborative cross-phase approach, something that we were able to facilitate on project development days.

Achieving word ownership through talk

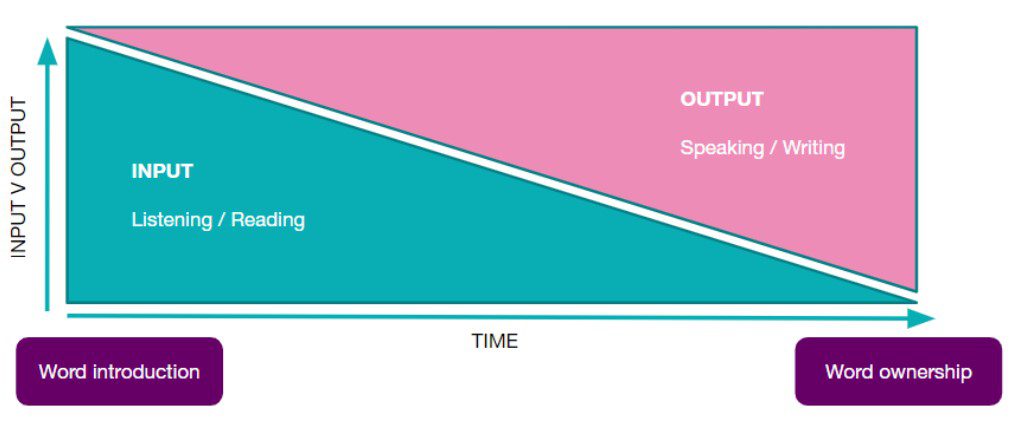

Learning new vocabulary takes time, as students are introduced to words and gradually move towards retention and production of new language (Beck et al., 2013). Participants were introduced to a simple framework (see Figure 1) to help to conceptualise this movement from word introduction to word ownership (Beck et al., 2013). Teachers considered the existing balance between spoken and written methods for introducing or consolidating new vocabulary, and evaluated their current lesson and curriculum planning, assessing where there was greater scope for vocabulary work to be driven by oracy.

Figure 1: Framework for transition from word introduction to word ownership

To support a shift from written to spoken modes of instruction, we introduced a range of strategies that support structured talk. Input activities were embedded in lessons where new language was being introduced, creating multiple opportunities for students to hear and begin using new vocabulary through exploratory talk (Barnes, 1992). Over time, students progressed to increasingly presentational output activities. These tasks were designed to provide students with opportunities to demonstrate their mastery of recently learned vocabulary and for teachers to assess the extent to which new language was embedded in students’ productive vocabulary.

Collaborating at transition

Developing sustained partnerships between teachers and schools has the capacity to improve the primary to secondary transition for students (Bromley, 2016), by creating better continuity of practice and more understanding of the language expectations across key stages. Studies of transition suggest that significant numbers of students experience disruption in academic outcomes during this time (Jindal-Snape et al., 2020). Linguistic challenges include an increase in polysemic language (Deignan et al., 2022), especially in subjects such as science.

As part of the project, each cluster of schools designed transition projects to be delivered in the summer terms of each year. These projects, focused on developing familiarity with vocabulary in science, maths, drama, geography and English, brought schools together to work on a series of lessons that would be delivered by Year 6 and Year 7 teachers. Sessions were designed to incorporate strategies explored on development days, creating an authentic context in which to embed newly acquired approaches to oracy and vocabulary teaching. Throughout the project, we collected insights on transition from student focus groups, which told us that students in participating primary schools were concerned about:

- making new friends

- having multiple teachers

- navigating a new and much bigger environment

- finding class and homework too hard, particularly in subjects such as science and mathematics.

These concerns resonate with existing research (Bromley, 2016), and while the Voicing Vocabulary project aimed to improve students’ academic vocabulary, we quickly understood that the transition projects would enable us to attend to multiple risk factors (Jindal-Snape et al., 2020) surrounding transition, by providing students with the opportunity to explore complex vocabulary, create relationships with new teachers and familiarise themselves with secondary school environments.

The impact so far

Literacy

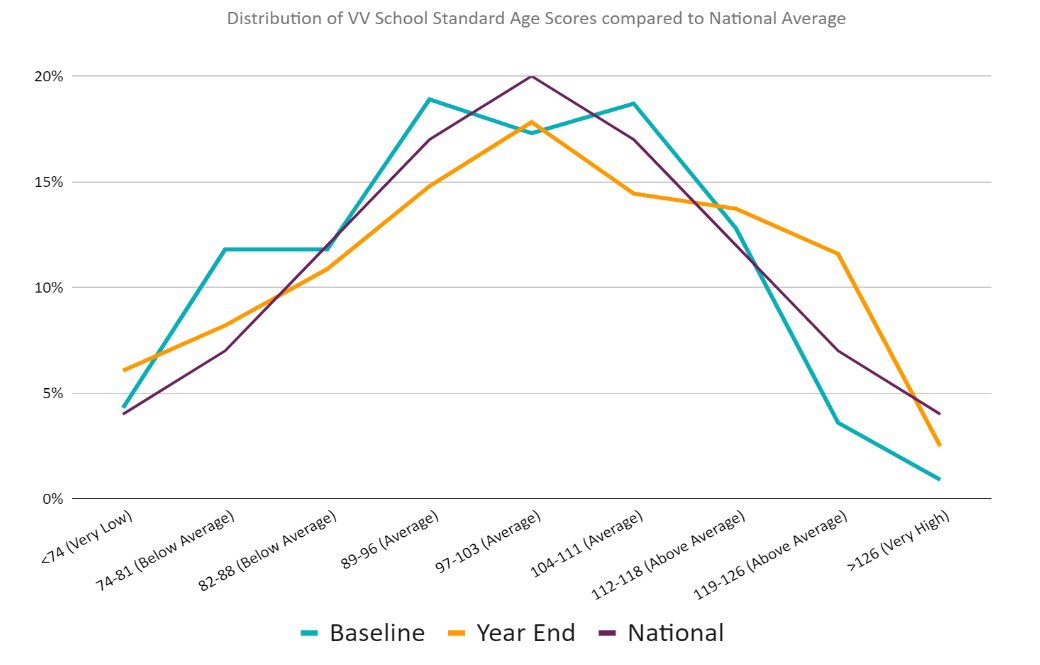

Analysis of data gathered through the New Group Reading Test (see Figure 2) in year one of the project shows that at the beginning of the year the percentage of students in participating schools who were above average was below the national figure. The end-of-year data, however, shows that the cohort we tested had a higher proportion of students scoring above average than the national average, supporting a correlation between spoken language and the development of students’ reading skills.

Figure 2: Analysis of data from the New Group Reading Test after the first year of the project

Teacher practice

The project has also led to changes in teacher practice, with one teacher commenting that:

Before we would think: what lessons do we want to do? What activities do we want to do? Then we’d think about which words fit into that. Whereas vocabulary now comes at the start. We plan now by identifying the Tier 2 and Tier 3 words we need to focus on and we’ll have perhaps five key words where we might have had 20 before.

(Year 5 teacher, Braunstone Frith Primary School, Leicester)

Additionally, survey results at the end of year one showed that teachers in participating schools developed greater confidence and competence as oracy practitioners. Teachers across the cohort improved confidence levels with oracy strategies by an average of 22 per cent from the beginning to the end of the first year of the project.

Implications for future practice

The Voicing Vocabulary project has enabled us to apply an oracy lens to existing research on vocabulary and transition and to better understand the impact of a talk-rich approach to vocabulary instruction on attainment. Equipping teachers with practical strategies to support curriculum planning and classroom talk has created a shared approach to vocabulary development in participating schools. While we are still in the process of collecting and analysing data from year two of the project, our early findings suggest that this approach could improve academic outcomes at Key Stage 3 and that, where possible, schools and teachers should be supported to both harness oracy for vocabulary development and build cross-phase relationships in order to better support the language demands of transition.

- Barnes D (1992) From Communication to Curriculum, 2nd ed. London: Heinemann.

- Beck, I, McKeown M and Kucan L (2013) Bringing Words to Life: Robust Vocabulary Instruction, 2nd ed. Guildford Press, New York.

- Beck I, McKeown MG and Omanson RC (1987) The effects and uses of diverse vocabulary instructional techniques. In: McKeown MG and Curtis ME (eds) The Nature of Vocabulary Acquisition. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, pp.147–163.

- Bromley M (2016) Key stage 3: The curriculum and working across phases. SecEd. Available at: www.sec-ed.co.uk/best-practice/key-stage-3-the-curriculum-and-working-across-phases (accessed 22 June 2023).

- De Vries R and Rentfrow J (2016) A winning personality: The effects of background on personality and earnings. Sutton Trust. Available at: www.suttontrust.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Winning-Personality-FINAL.pdf (accessed 22 June 2023).

- Deignan A, Candarli D and Oxley F (2022) The Linguistic Challenge of the Transition to Secondary School: A Corpus Study of Academic Language, 1st ed. Routledge, London.

- Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) (2021) Teaching and Learning Toolkit. Available at: https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/education-evidence/teaching-learning-toolkit (accessed 22 June 2023).

- Gascoigne M and Gross J (2017) Talking about a generation. The Communication Trust. Available at: https://speechandlanguage.org.uk/media/3215/tct_talkingaboutageneration_report_online_update.pdf (accessed 22 June 2023).

- Harris J and Nowland R (2021) Primary–secondary school transition: Impacts and opportunities for adjustment. Journal of Education on Social Science 8: 55–69.

- Howe C, Hennessy S, Mercer N et al. (2019) Teacher–student dialogue during classroom teaching: Does it really impact on student outcomes? Journal of the Learning Sciences 28: 462–512.

- Jindal-Snape D, Hannah EFS, Cantali D et al. (2020) Systematic literature review of primary‒secondary transitions: International research. Review of Education 8(2): 526–566.

- Mercer N and Hodgkinson S (2008) Exploring Talk in School: Inspired by the Work of Douglas Barnes. London: Sage Publications.

- Mercer N, Warwick P and Ahmed A (2017) An oracy assessment toolkit: Linking research and development in the assessment of students’ spoken language skills at age 11–12. Learning and Instruction 48: 51–56.

- Nation ISP (2001) Learning Vocabulary in Another Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Oracy All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) (2021) Speak for change. Available at: https://oracy.inparliament.uk/files/oracy/2021-04/Oracy_APPG_FinalReport_28_04%20%284%29.pdf (accessed 22 June 2023).

- Quigley A (2018) Closing the Vocabulary Gap, 1st ed. Routledge, London.

- Voice 21 (2019) The Oracy Benchmarks. Available at: Benchmarks-report-FINAL.pdf (voice21.org) (accessed 28 June 2023).