The Writing Game: Can gamified activities aid pupils’ writing skills?

Robin Hardman, Politics teacher, Hampton School, UK

As any humanities or social science teacher will know, there is a common paradox underpinning many teenagers’ attitudes towards academic writing: while most students recognise that the ability to write cogently will be central to their success in public examinations and the world of work, they are often reluctant to engage in the deliberate practice required for development.

Many schemes of work simply perpetuate the problem, confining writing practice to high-stakes assessments that blur the boundaries between subject knowledge and the application of writing techniques, and providing too few opportunities for low-stakes practice in which students can make mistakes without suffering any adverse consequences.

In a bid to address these issues, I have introduced a range of gamified writing activities in my politics A-level teaching in recent years, with the following aims: increasing students’ motivation to practise academic writing in lessons and in their own time; using incentives to highlight key writing skills; and providing more frequent opportunities for low-stakes writing practice in order to drive improvement.

Gamifying writing development

Gamification refers to the use of game design elements – such as low-stakes competition, progression through levels of increasing difficulty, and visible recognition of players’ status – in non-game contexts (Deterding et al., 2011). Increasingly prevalent in classroom practice and sports coaching in recent years, the adoption of gamified strategies in writing skill development offers several possible affordances, including but not limited to: increased opportunities for formative assessment; improvements to students’ engagement and motivation levels; and the creation of meaningful narratives to encourage self-regulation and independent practice (Dicheva et al., 2015; Gee, 2005; Ramirez and Squire, 2014).

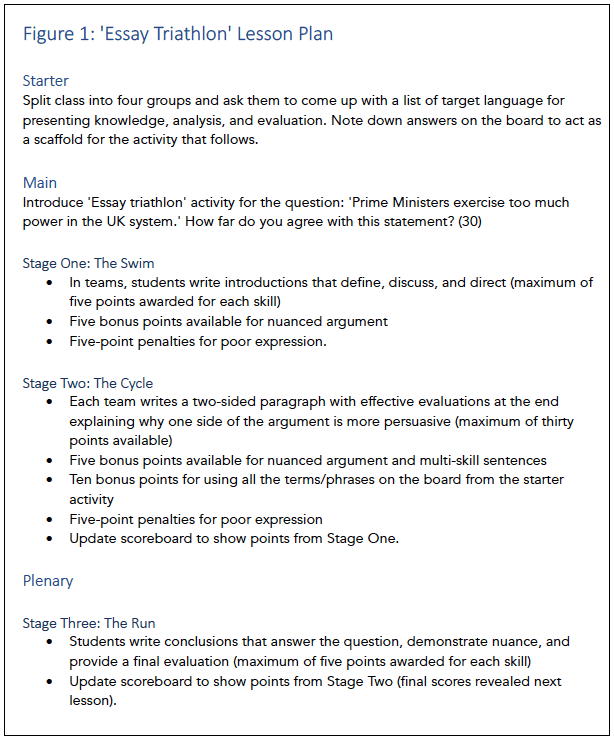

My own experiences have suggested that gamifying writing skills improves both students’ engagement levels and their attainment. Competitive group writing tasks (example lesson plan in Figure 1) have seemed particularly effective, offering chances for focused yet enjoyable low-stakes writing practice. Likewise, an Antiques Roadshow-inspired ‘Basic, Better, Best’ modelling exercise, where students identified why certain essay excerpts were more sophisticated than others, appeared to boost their metacognitive understanding of what excellent writing constitutes. In both instances, I felt that applying gamified elements through the construction of themed narratives and the use of points-based scoring systems produced a more dynamic lesson framework than traditional, non-competitive group writing or modelling exercises.

Download a Microsoft Word version of Figure 1: ‘Essay Triathlon’ Lesson Plan

Wary of falling foul of the ‘edutainment’ curse, though, I wanted to investigate whether my experiences were supported by evidence-based research. While there has not yet been any published academic literature evaluating the effectiveness of gamified activities in supporting adolescents’ writing development, there are multiple areas of consistency between the emergent research findings on gamification and the insights of more established discourse on teaching strategies in general and writing development specifically: namely, the importance of rapid feedback, low-stakes practice and the freedom to fail.

Sandboxes

Research focusing on both gamification and writing skills highlights the importance of frequent low-stakes, formative assessment to aid students’ progress towards long-term learning goals. Gee (2005, p. 12) likens gamified activities to ‘sandboxes’, placing learners in ‘a situation that feels like the real thing, but with risks and dangers greatly mitigated, [where] they can learn well and still feel a sense of authenticity and accomplishment’. This is echoed by Troia (2014, pp. 13–14), who notes that ‘when students spend more time in sustained writing activities and/or write more frequently, they have greater opportunities to practice their writing skills and strategies for composing’.

Reframing writing practice by incorporating elements of game design provides a means through which teachers can create chances for students to experiment and make mistakes, without the pressure of a summative assessment, but with a degree of incentivisation that traditional skill practice often lacks. I have integrated gamified ‘sandbox’ activities in my schemes of work for each A-level topic, scheduling competitive group writing tasks approximately a week before more traditional timed assessments. While students naturally still encounter difficulties in the formal assessments that follow the gamified activities, they are often better equipped to solve problems as a result of their prior practice.

Academic literature in both fields also supports the concept of group writing activities: in their meta-analysisA quantitative study design used to systematically assess the results of multiple studies in order to draw conclusions about that body of research of research-based writing practices, Graham et al. (2015, p. 509) report that ‘having students work together when writing was common among exceptional literacy teachers’, while Rabah et al. (2018, p. 4) note that ‘gamification aids in building communities, where participants share tips and celebrate accomplishments on a whole class level, not only academic high-achievers’. I have witnessed the power of these ‘communities’ in my own classroom: when group writing activities are reframed as games with meaningful incentives, students are encouraged to learn from each other, discussing sentence construction, vocabulary choice and subject-specific terminology far more frequently than they would in an ordinary lesson. Moreover, the competitive nature of the activities seems to be effective in building a collaborative team spirit that encourages pupils to share their expertise with each other.

Although it would be impossible without sustained additional research to assess the impact of gamified group writing activities on attainment, my impression has been that they have expedited my students’ understanding of, and ability to apply, the hallmarks of high-quality A-level essay writing. Typically, in the past, I would have expected the majority of my students to master essay technique in their upper sixth year, whereas many essential components of successful writing – nuanced arguments, fully-formed evaluations and multi-skill sentences – are now increasingly visible in lower sixth students’ work.

Visualised progress

Similarly, research on both gamification and writing development acknowledges the centrality of motivation to the learning process. While it is important to bear in mind Nuthall’s (2007, p. 35) maxim that ‘learning requires motivation, but motivation does not necessarily lead to learning’, gamification does seem to offer a particularly enticing panoply of possibilities for increasing students’ engagement with and motivation for undertaking skill practice, both in lessons and through independent study: Ramirez and Squire (2014, p. 631) state that gamification provides ‘visualised progress’ and ‘rapid feedback’ as learners progress through ‘levels’.

I have tried to harness these elements of game design in my A-level lessons. In an activity dubbed ‘Essay doctors’, students are asked to diagnose problems with essay extracts and suggest how these issues could be overcome. The diagnoses – and their cures – increase in difficulty over the course of the task, with students having the chance to rise from the lowest ‘medical students’ level to the highest rank of ‘Chief Medical Officer’. As with the other gamified strategies identified previously, I have found that students are more motivated to make progress – both towards task completion and towards accurate application of knowledge – in the ‘Essay doctors’ activity than in more traditional peer-assessment tasks, which often seem to be regarded as rather anodyne.

By offering students the chance to measure and understand their own progress, gamified activities have the potential to improve motivation, which Hayes’s (2012, p. 373) model regards as the crucial determinant of writing skill development: ‘whether people write, how long they write, and how much they attend to the quality of what they write will depend on their motivation.’ In addition to the lesson activities mentioned above, I have tried to encourage students to monitor their own writing development with a homework activity called ‘Target zone’, in which they identify goals arising from previous written work; if students manage to achieve these targets in their next essay, I reward them with ‘panini points’, my school’s equivalent of merits for sixth formers.

Conclusions

Gamifying writing development should not be considered a panacea to the widespread perception that skill practice is a less dynamic and valuable lesson component than course content. However, gamification offers multiple possible affordances that ought to be further explored in academic literature. While its role in aiding students’ motivation and engagement has thus far been the primary focus of most research, the possibilities that it entails for formative, low-stakes assessment and collaborative writing are manifold and significant.

Research has emphasised gamification’s capacity for transforming tasks perceived as boring into interesting ones. If teachers can infuse gamified elements into activities – such as modelling, goal setting and peer-assessment – that have been proven to boost writing development, the potential benefits to students’ engagement, metacognition and cognitive outcomes are too great to ignore.

References

Deterding S, Dixon D, Khaled R et al. (2011) From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining gamification. In: Proceedings of the 15th international academic mindtrek conference: Envisioning future media environments, Tampere, Finland, 28–30 September 2011, pp. 9–15.

Dicheva D, Dichev C, Gennady A et al. (2015) Gamification in education: A systematic mapping study. Journal of Educational Technology & Society 18(3): 1–14.

Gee JP (2005) Learning by design: Good video games as learning machines. E-Learning 2(1): 1–16

Graham S, Harris KR and Santangelo T (2015) research-based writing practices and the common core: Meta-analysis and meta-synthesis. The Elementary School Journal 115(4): 498–522.

Hayes JR (2012) Modeling and remodeling writing. Written Communication 29(3): 369–388.

Nuthall G (2007) The Hidden Lives of Learners. Wellington: NZCER Press.

Rabah J, Cassidy R and Beauchemin R (2018) Gamification in education: Real benefits or edutainment? In: ECEL 2018 17th European conference on e-learning (eds K Ntalianis, A Andreatos and C Sgouropoulou), Athens, Greece, 1–2 November 2018, pp. 489–496.

Ramirez D and Squire K (2014) Gamification and learning. In: Walz SP and Deterding S (eds) The Gameful World: Approaches, Issues, Applications. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, pp. 629–652.

Troia G (2014) Evidence-based practices for writing instruction. Available at: https://ceedar.education.ufl.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/IC-Writing.pdf (accessed 6 May 2020).

Figure 1 link to illustration broken. Please reinstate. Thanks.

Hi Alison, thanks for pointing this out. Figure 1 has now been added again.