In awarding grades, we must recognise the significant disruption students have faced

This viewpoint on Ofqual’s proposals regarding summer examinations in 2021 is written by Shirley Clarke, Former Primary Teacher, Lecturer and Researcher, Fellow of the Chartered College, and an internationally-renowned expert in the application of formative assessment in practice.

The views presented here do not necessarily represent those of the Chartered College. Views on the best way forward are very varied across the sector. For a different viewpoint, read Michael Chiles’ thoughts and Mick Walker’s views, and for a wider perspective on some of the challenges and our members’ views, have a look at Cat Scutt’s summary of members’ concerns for the Chartered College.

If we look at the experience so far of last year’s Year 10 students who are now in Year 11, and Year 12 now Year 13, they have had more disruption to their education than any other year in living memory since World War II. I have a daughter, Katy, in Year 11, so it is useful that I can give one student example of this entire experience, even though that will not necessarily be the same experience for every Year 11 student: the profound lack of equity which characterises the education experience during the pandemic.

Katy’s perspective

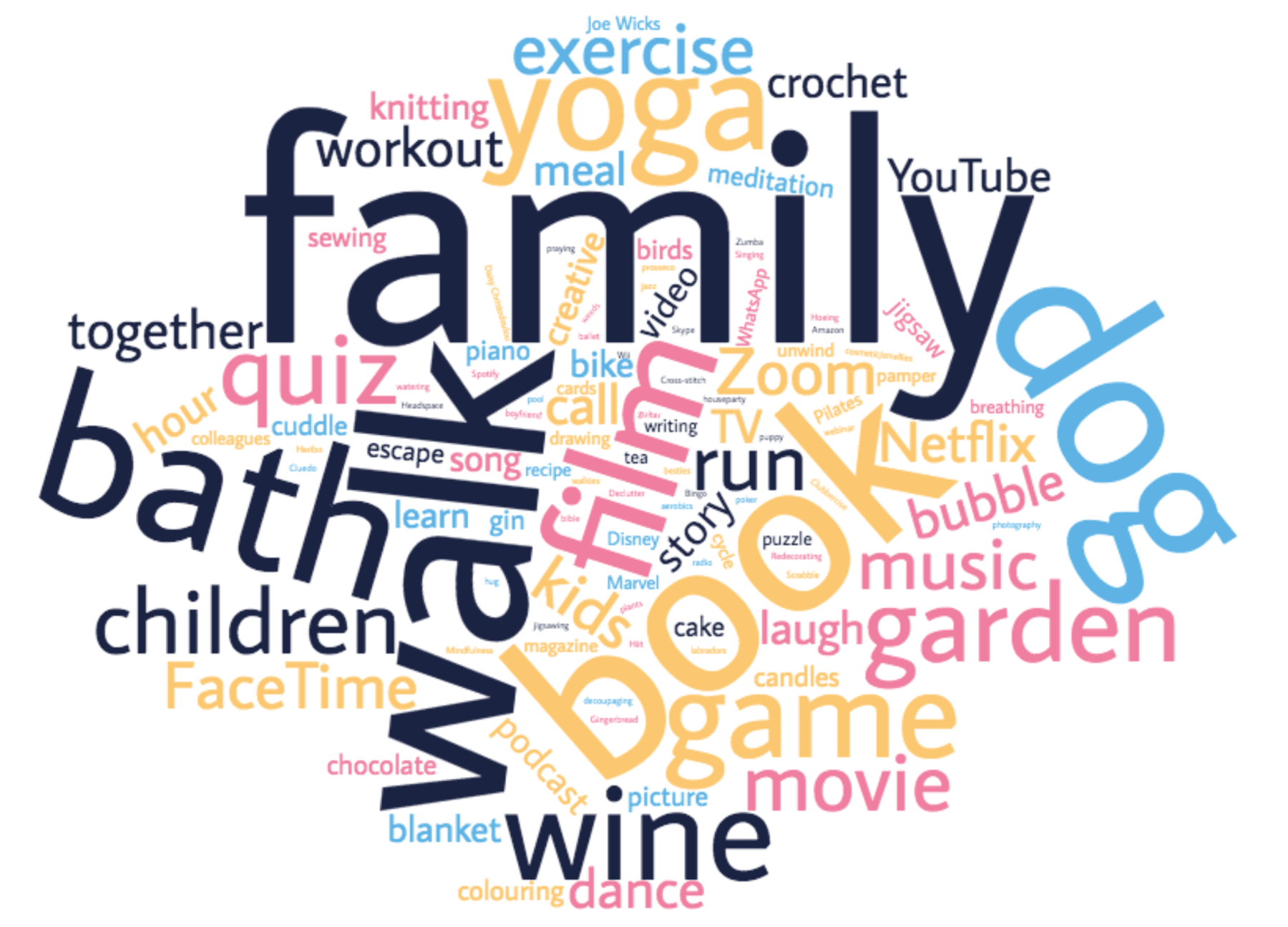

Katy’s opinions about Ofqual’s recommendations were passionately voiced. Her first point was the utter hopelessness experienced by her year group, feeling constantly unclear about how they will be assessed, whether and when they will be at school, what they should study, if anything, and how their whole life could be affected by people who had never experienced what they are experiencing. Their mental health is suffering: being cooped up, not seeing friends, worrying about loved ones becoming ill or dying, being overwhelmed with remote learning and homework, feeling the pressure of this important year but not knowing what will happen to them or their futures.

Katy’s second point was that remote lessons cannot compare to real teaching. She feels as if she has not been sufficiently taught for months, even though teachers are doing their very best to make it work, because the remote experience is so totally inferior. For safeguarding reasons, cameras must be turned off and audio muted in case of ambient noise, so they spend the lesson in isolation listening to a teacher and possibly seeing the teacher’s slides. Students type when asked in the chat box but they also text each other during lessons and leave to get snacks or for toilet breaks, inevitable when they can’t be seen or heard. Some students just don’t (or can’t, for a range of reasons) turn up for the lessons. Some can’t consistently check emails from the teachers to see when live lessons are scheduled and how to connect to them.

Any kind of exam, whether a mock GCSE or slimlined ‘paper ’ as proposed was met with horror, because of the lack of teaching and missed school. Katy made the important point that slimmed down content would mean there would be higher expectations placed upon students because having less to revise they ‘should’ do better , whereas greater content would yield lower expectations, as there is far more to revise, but be unfair because of the lack of schooling.

So what are the issues as I see them?

- The devastating impact of the pandemic on our children’s mental health – it can’t be separated from their ability to perform as they would have done had there not been a pandemic.

- Remote teaching is vastly inferior compared to face-to-face teaching and the impact therefore on students’ ability to fully understand the learning.

- The quest for validityIn assessment, the degree to which a particular assessment measures what it is intended to measure, and the extent to which proposed interpretations and uses are justified in awarding teacher assessed grades – whether through in-school exams, external ‘papers’ or ongoing homework, students are unlikely to get the grades they would have received because of the lack of face-to-face teaching. It would be like someone taking a driving test when they had not had enough driving lessons on the road in real conditions, but were instead using computer simulators to ‘drive’.

- The quest for reliabilityIn assessment, the degree to which the outcome of a particular assessment would be consistent – for example, if it were marked by a different marker or taken again between teachers’ judgements – unless grade boundaries are set in advance, and take into account lost teaching time, teachers will not know whether to give grades for achievement as it is at this moment, or what it could have been. If this does not happen, teachers will be inconsistent in their approach as they strive to not penalise children for lost teaching time.

The best option seems to be ongoing teacher assessment, based on what teachers are seeing in students’ work, bearing in mind that without normal classroom interaction the work is unreliable, or at least is likely to be of a lower standard than if there had been schooling. What is a teacher to do, however, if they know a student had limited access to a laptop, or a peaceful environment, or was self-isolating during the short time schools were open? For all of these reasons, it will be important for grade boundaries to be lowered, in effect allowing teachers to predict what the student would probably have attained had there not been a pandemic. This was, in the consultation document, not recommended, but if students are to come away with appropriate grades it has to be so. The likely outcome if grade boundaries are not lowered – whether or not teachers have to set exams or consider ongoing assessment – will be that all students will receive a grade, by my estimation, up to two grades lower than they would have received in normal circumstances. This is due to the lack of face-to-face teaching, coupled with the stress of the pandemic, meaning that students are unlikely to be able to demonstrate what they would have known, understood and been able to accomplish.

My proposals

No externally set ‘papers’, whether optional or compulsory, because the great loss of teaching time and the mental health issues put all students at a disadvantage. At this time, there is a great possibility that students will not return to school until after Easter or even May. This means that revision time is unknown for any kind of exam. The one constant will have been students’ ongoing homework and assessment throughout the closures, so using this information seems fairer.

No in-school ‘mocks’, unless they are marked according to the adjusted grade boundaries, although students are still unlikely to perform as they would have done if there had not been a pandemic.

Publication to schools of adjusted grade boundaries which take into account lost teaching time, students’ lack of access to WiFi/computers and their mental health.

Published exemplars of grades 1-9, which have been adjusted accordingly.

Compulsory moderation between teachers in departments, using these exemplars, then teachers to be trusted.

The timing for awarding the grades should be as late as possible, to allow for even the slightest rise in attainment, although it should be acknowledged that many students are getting further and further behind, with the resulting decreased self-efficacy and motivation.