Staff experiences of pupils’ self-harming behaviour in an independent girls’ boarding school

Emma Margrett, Head of the Prep School, Radnor House, Sevenoaks, UK

Background

In recent years, a number of pieces of research have been published that suggest that self-harm in adolescence is increasing (Hall and Place, 2010; Beauchaine et al.,2014; Garcıa-Nieto et al., 2015). Heath et al., (2006) found that a majority of school teachers shared this view. In their study, 74 per cent of teachers surveyed reported a first-hand encounter with self-injury in school. The topic of self-harm is receiving more coverage in mainstream media (Dutta, 2015; Money-Coutts, 2015), suggesting a rise in public consciousness around mental health issues including self-harm. The extent of mental health problems among adolescents has also been publicly acknowledged by the Department of Health, who stated in 2015 that ‘over half of mental health problems in adult life (excluding dementia) start by the age of 14 and seventy-five per cent by age 18’ (Department of Health, 2015, p. 9).

Research into adolescent self-harm has suggested that the most likely age for adolescents to commence self-harm is within the 10-15 years age bracket (Garcıa-Nieto et al., 2015; Hanania et al., 2015), revealing that many adolescents are self-harming at an age where they are expected to be in school for the majority of their time. However, in studies of teachers, a ‘patchy’ awareness of self-harm has been demonstrated (Best, 2005a; 2005b), and a lack of ability to know how best to deal with the situation, should it present itself, has been acknowledged by teachers in a number of research articles (Hall and Place 2010; Heath et al. 2006; Kidger et al., 2010). My research was guided by two main questions; firstly, what are the experiences of independent school staff of pupil disclosures of self-harm? And secondly, how well equipped do independent school staff feel to deal with pupil disclosures of self-harm?

Literature review

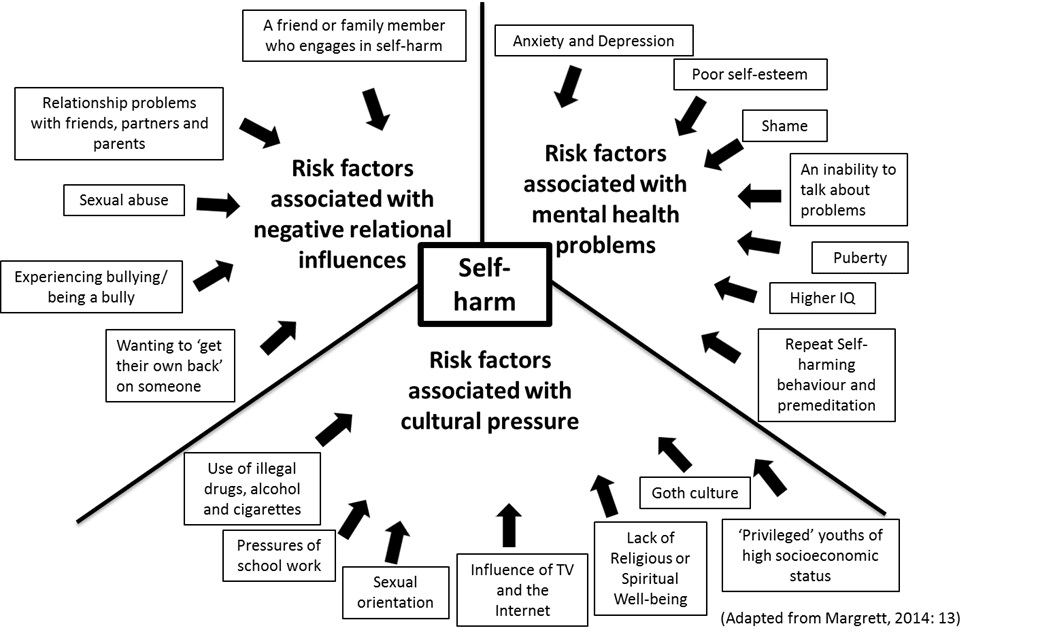

My initial literature review was conducted through a Boolean search, searching specifically for key terms including self-harm, self-injury and NSSI (non-suicidal self-injury). I used the ASSIA database to search for articles which had been published between January 2000 and March 2014, followed by an interrogation of the bibliographies of relevant articles to look for key papers which may have been published before this period. This initial search yielded 838 results with articles further reduced to those focused primarily on adolescents attending mainstream schooling and undergraduate courses, who had not been treated as long term in-patients for their self-harming behaviour, and who were from predominantly western parts of the world such as the United Kingdom, Europe, the United States and Scandinavia. The same Boolean search was conducted in July 2016, focusing on articles which had been published between March 2014 and July 2016, producing an additional 207 articles, with articles being reduced in a similar way. The literature review identified the risk factors associated with self-harm, which are outlined in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Risk factors associated with self-harm

Methodology

Semi-structured, qualitative, individual interviews, following a common, pre-identified set of open-ended questions, were then conducted with four subject teachers, two housemistresses and a school matron in one girls’ independent boarding school. I asked the same set of questions in each interview, and depending on the responses, discussions generally lasted from 30 minutes to one hour. As Mann (2003, p. 66) argues, ‘qualitative approaches enable the researcher to take an open-ended, exploratory approach where little is predetermined or taken for granted’. This may be particularly important when addressing an issue such as self-harm where understandings of the term are varied.

Once conducted, the interviews were analysed through the use of Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) (Smith, Flowers and Larkin, 2013) and findings were synthesised with some of the key concepts found in the work of Foucault (Dreyfus and Rabinow, 1983; Foucault, 1991) concerning discourses of power, knowledge and truth. The work of Foucault links well with the concept of self-harming behaviour because Foucault considered how society used the body as a means to exercise control over the individual. For Foucault, the body is ‘a site where regimes of discourse and power inscribe themselves’ (Butler, 1989, p. 601). Foucault sees the body as ‘invested by power relations’ (Foucault, 1991, p. 24), arguably leading to a situation where people conform to the norms of society because they feel under public pressure to do so.

The IPA approach allows the researcher to analyse interview transcripts to try and identify the superordinate themes that run through a number of individual narratives, suggesting a common experience shared by a number of research participants. However, a feature of IPA is also the need for a researcher to be fully aware of each person and how they are situated in the world before making more overarching claims about the essence of their experience. This appealed to me because I had chosen to research as an insider researcher with colleagues. I was therefore particularly aware of each participant in their own right, and I wanted to show their individual stories and experiences the respect I felt they deserved. Brocki and Wearden (2006) suggest that by adopting IPA, a researcher is at the very least tacitly accepting their interpretative role, and this is a stance which resonates with my own understanding of my research. However, although I acknowledge that my interpretation may be one of many different ways of understanding the data I have collected, this should not negate the validityIn assessment, the degree to which a particular assessment measures what it is intended to measure, and the extent to which proposed interpretations and uses are justified of my research. Yardley (2000) suggests that reliabilityIn assessment, the degree to which the outcome of a particular assessment would be consistent – for example, if it were marked by a different marker or taken again and replicability is an inappropriate criterion to judge qualitative researchQualitative research usually emphasises words rather than quantification in the collection and analysis of data. against because, by definition, qualitative analysis attempts to offer one possible interpretation of a phenomenon rather than proposing the sole method of understanding what has been experienced.

As there was little literature already available on the subject of staff experiences of pupils who self-harm in an independent school, the experience of each individual is key to shedding light on the phenomenon of adolescent self-harm in independent schools, and as self-harm is such a personal experience, I argued that the recognition of each individual’s unique life story is important. I also felt that it was imperative to analyse the transcripts of the interviews in detail to ensure that the representation of the interview is as accurate as possible. In my study, the confidence that the representation of interviews is as accurate as possible is further enhanced by the fact that I sought confirmation from my participants that they were happy with the way that I had analysed the transcripts of their interviews before using them as part of my analysis.

Key findings

The study found that within the small sample interviewed, the participants demonstrated a lack of confidence in their own understanding of the term ‘self-harm’, but had a wide experience of pupil self-harm disclosures. While risk factors identified by staff were largely similar to those already identified in the self-harm literature, a notable addition was the suggestion that self-harm may be performed as a response to a fear of failure exacerbated by over-parenting and spoon-feeding by teachers, potentially caused by the ever increasing demands on both parents and schools to become more involved in the lives of their pupils whilst producing outstanding examination results and achieving cultural expectations. This idea is supported by the work of Dweck (2008, 2012), Lahey (2015) and Brummelman et al. (2013, 2014).

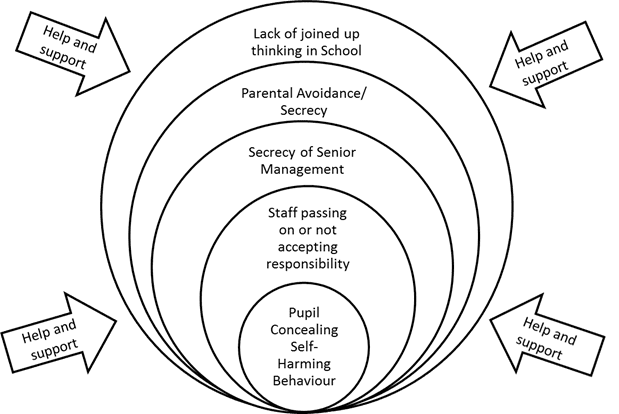

The hidden nature of self-harm

One superordinate theme which recurred in every interview was the hidden nature of self-harm. The essence of self-harm being a hidden phenomenon manifested itself in a number of different ways. There was the hidden nature of the pupils’ injuries and the secrecy of the behaviour of pupils who were self-harming; the issue of staff passing on or not accepting responsibility for dealing with the issue of a disclosure of self-harm; the unwillingness to engage with self-harm as a serious issue by some key staff and by the parents of pupils who were engaging in self-harm; the secrecy of senior management concerning how the issue was being dealt with after the referral once an instance of self-harm had been reported by a member of staff; and finally a lack of ‘joined-up’ thinking between staff once a disclosure of self-harm had been made. This led to the idea of concentric circles of complicit secrecy surrounding the pupil in the centre, each layer making it more difficult for them to receive effective external help and support (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Circles of secrecy surrounding a pupil exhibiting self-harming behaviours

This suggested that there was a cultural context in the school which underpinned the idea that self-harming behaviour should not be discussed openly and publicly, which unfortunately allowed the culture of secrecy surrounding self-harm to prevail. It seems that there is a social stigma attached to admitting that self-harming behaviour is occurring within your school. This links to Smail’s point that society is conditioning its members to look down on those who deviate from the norms of acceptable behaviour (Smail, 2015), and the need identified by Goffman for people to convey an image to others that it is in their interests to convey (Goffman 1959). Foucault (1991, p. 189), might suggest that within the ‘field of surveillance’, schools are feeling the pressure to achieve what is perceived to be the norm as a minimum. They cannot admit to self-harming behaviour taking place within their environment because it could suggest that their school is performing less well than other schools, although the sad reality is that pupils are engaging in self-harming behaviour in almost every classroom in the country (Best, 2005a; MHF, 2006).

Key practical implications for teachers, leaders and support staff

A key theme which emerged from the study was the need for the training of all staff, not just key pastoral staff, in dealing with pupil disclosures of self-harm, due to the fact that it may not be those staff to whom pupils choose to disclose. Additionally, the findings clearly revealed the requirement for schools to develop a discrete but explicit self-harm policy (Robinson et al., 2008) containing clear guidelines for referral and follow-up of disclosures of self-harm, in order to address the fact that many staff felt ill-equipped to deal with pupil disclosures of self-harming behaviour. Finally, the study supported the need for supervision style meetings to be made available for school staff to have the ability to discuss their own anxieties and concerns around pupil disclosures (Best, 2005a, 2005b), because staff members do not always have the necessary support systems in place to allow their concerns to be aired.

Recommended further reading

Margrett EL (2017) Staff experiences of pupils’ self-harming behaviour in an independent girls’ boarding school: an IPA analysis. A Doctoral thesis (EdD). Sussex: University of Sussex. Available at: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/68112/1/Margrett%2C%20Emma%20Louise.pdf (accessed 31 October 2022).

References

- Beauchaine TP, Crowell SE and Hsiao RC (2014) Post-Dexamethasone Cortisol, Self-Inflicted Injury, and Suicidal Ideation Among Depressed Adolescent Girls. Journal Abnormal Child Psychology 43: 619–632.

- Best R (2005a) Self-Harm: A Challenge for Pastoral Care. Pastoral Care in Education 23(3): 3–11.

- Best R (2005b) An Educational Response to Deliberate Self-Harm: Training, Support and School Agency Links. Journal of Social Work Practice: Psychotherapeutic Approaches in Health, Welfare and the Community 19(3): 275–287.

- Brinkmann S and Kvale S (2005) Confronting the ethics of qualitative research. Journal of Constructivist Psychology 18(2): 157–181.

- Brocki JM and Wearden AJ (2006) A critical evaluation of the use of interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) in health psychology. Psychology & Health 21(1): 87–108.

- Brummelman E, Thomaes S, Orobio De Castro B et al. (2014) That’s Not Just Beautiful—That’s Incredibly Beautiful! Psychological Science 25(3): 728–735.

- Brummelman E, Thomaes S, Overbeek G et al. (2013) On feeding those hungry for praise: Person praise backfires in children with low self-esteem Journal of Experimental Psychology 143(1): 9–14.

- Cohen L, Manion L and Morrison K (2005) Research Methods in Education, Routledge Falmer: London.

- Dreyfus H and Rabinow P (1983) Michael Foucault: Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Dutta K (2015) Teaching unions warn of self-harm epidemic among students. The Independent, January 7, 2015.

- Dweck C (2012) Mindset: How You Can Fulfil Your Potential. London: Robinson.

- Dweck C (2015) The Secret to Raising Smart Kids. Scientific American Mind, January 1, 2015.

- Foucault M (1991) Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. London: Penguin.

- Garcıa-Nieto R, Carballo JJ, Dıaz de Neira Hernando M et al. (2015) Clinical Correlates of Non-Suicidal Self-Injury (NSSI) in an Outpatient Sample of Adolescents. Archives of Suicide Research 19: 218–30.

- Geertz C (1973) The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays, Basic Books: New York Goffman E (1959) The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. London: Penguin.

- Hall B and Place M (2010) Cutting to cope – a modern adolescent phenomenon. Child: Care, Health and Development 36(5): 623–629.

- Hanania JW, Heath NL, Emery AA et al. (2015) Non-Suicidal Self-Injury among Adolescents in Amman, Jordan. Archives of Suicide Research 19(2): 260–274.

- Heath N, Toste J and Beettam E (2006) I Am Not Well-Equipped: High School Teachers’ Perceptions of Self-Injury. Canadian Journal of School Psychology 21: 73–92.

- Kidger J, Gunnell D, Biddle L et al. (2010) Part and Parcel of teaching? Secondary school staff’s views on supporting student emotional health and wellbeing. British Educational Research Journal 36(6): 919–935.

- Lahey J (2015) The Gift of Failure: How to step back and let your child succeed. London: Short Books.

- Mann C (2003) Analysis or anecdote? Defending qualitative data before a sceptical audience in Hughes C (ed) (2003) Disseminating Qualitative Research in Educational Settings: a critical introduction. Glasgow: Open University Press.

- Mental Health Foundation (2006) Truth Hurts: Report of the National Inquiry into Self-harm among Young People. London: Mental Health Foundation.

- Money-Coutts S (2015) The self-harm epidemic. Tatler, 5 October, 2015. Available

- Public Health England (2015) Promoting children and young people’s emotional health and Wellbeing: A whole school and college approach.

- Robinson J, Gook S, Pan Yuen H et al. (2008) Managing deliberate self-harm in young people: An evaluation of a training program developed for school welfare staff using a longitudinal research design. BMC Psychiatry 8: 75.

- Smail D (2015) Taking Care, An Alternative to Therapy. London: Karnac Books.

- Yardley L (2000) Dilemmas in qualitative health research. Psychology and Health 15: 215–228.