Student agency and sustainability

Introduction

Agency, defined by the Cambridge Dictionary as ‘the ability to take action or to choose what action to take’ (n.d.) refers in an educational context to the ability to determine one’s own learning goal and the process of pursuing that goal (Vaughn, 2018). Agency may be used in a moral, social, economic, or creative context, shaping our interactions with ourselves and others (OECD, 2019). Because agency offers us the ability to self-reflect, self-react, and have forethought to make an action happen (Taub et al., 2020), out-of-classroom environments in particular may create a setting for meaningful learning and interaction between students and teachers (Kangas et al., 2014). Furthermore, being allowed and having the courage to question what one has learned is an important part of agency development (Vaughn, 2018).

Student agency has particular relevance in the context of sustainability, a topic that children and young people are increasingly concerned about. I believe that agency in younger generations is important in a world where adults are making political and economic decisions that will influence their lives. Climate change, and more broadly sustainability, have made the development of student agency all the more important. I got the opportunity to explore the concept of student agency in relation to climate change and sustainability at the end of 2021, when I was invited by Schools of Tomorrow with their partners at the Edge Foundation to help organise their first Sustainable Education Summit in Birmingham, UK. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, the summit was held in two parts – an online event in March 2022 followed by an in-person event in November. The summit was aimed at bringing school leaders and their student leaders together to look at a more sustainable approach to education in their schools. This article reflects on the summit and what we can learn about student agency in relation to sustainability in out-of-school settings.

Context

Schools of Tomorrow is a small, voluntary cross-phase network of schools in England and Europe committed to sharing a broader understanding of school purpose. It regularly involves students and school leaders in its work and in the post-COVID-19 world has established a new program – Ambassadors of Tomorrow – in partnership with the Comino Foundation. Over the last five years, my own studies in marine biology and climate change brought me to the topics of science education, sustainability, and student agency. I based my Master’s thesis on the concept of student agency at the Sustainable Education Summit with a particular focus on two questions:

- Do students feel heard and that their voices and interests regarding sustainability are being respected in the current school system?

- Do the findings indicate student agency in the participants?

I used the Model of Educational Reconstruction (MER) to frame my analysis of how students showed agency during the event. The MER is a framework that is widely used in science education research, particularly in Europe. It was designed to better understand the process of knowledge acquisition and reflect on science learning and instructional environments for both students and teachers (Duit et al., 2012). The model focuses on three key interrelated factors: design and evaluation of the learning environment, clarification and analysis of science content structure, and analysis of perspective and learning processes.

Design and evaluation of the learning environment

This part of the MER focuses on the development of tools and visualisations to simplify conceptual understanding and support the clarification of scientific content (Niebert and Gropengiesser, 2013). Data from the online event was analysed and used for reflection on the event design and to identify improvements for the in-person event.

Clarification and analysis of science content structure

This part of the MER focuses on the science content that is selected and embedded in a learning environment and how it is presented. The summit included a keynote speech by Professor Robert Barratt from the University of Lancaster on sustainability, narration and storytelling, equity, and sustainable innovation. The keynote was delivered in a classical lecture style. While education should, to improve student agency, be more participatory, with content co-created and students feeling ownership of their study (Corres et al., 2020; Vaughn, 2018; Vaughn, 2020; Cavagnetto), the keynote format was chosen to create a basis for discussion and more participatory activities throughout the day.

The student attendees, aged between 12 and 16, showed a high level of agency by questioning aspects of the speech. Comments such as ‘The logistics of tearing down buildings and rebuilding in nature does not seem feasible to me in terms of space and resources, and even attitudes’ indicate critical reflection on the content.

Analysis of perspective and learning processes

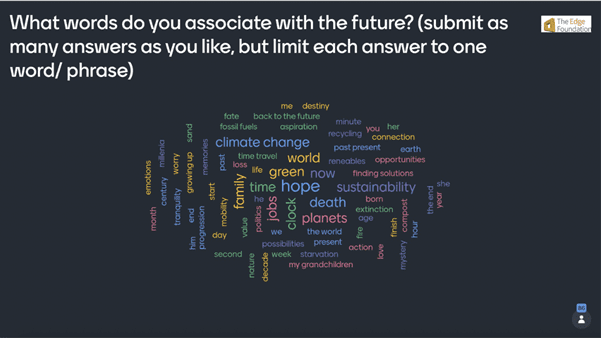

This part of the MER is concerned with the role of the students’ empirical knowledge and their learning processes. Students’ empirical knowledge, interests, and attitudes all play a part in how receptive they are to content (Duit et al., 2012). Mentimeter was used to gather insights from the students about their knowledge of, and attitudes towards, climate change and sustainability. A Mentimeter word cloud was created around the question ‘What words do you associate with the future?’. The question received a total of 86 very diverse answers. Students could submit multiple answers, the requirement being to use a maximum of two words.

As seen in the word cloud (Figure 1) students showed a mixed outlook toward the future. The words they chose indicated extensive knowledge of the problems connected to sustainability and climate change and the possibilities that we, as a society and individuals, continue to face. Students brought vast knowledge to the activities in both the online and in-person event – something that we as organisers had not expected. This perhaps indicates the shift in climate awareness in young adults over the last years and our underestimation of the student’s existing knowledge base. The questions students asked showed a strong understanding of the problems at hand, highlighting the need for a safe space for discussions that go deeper into the complexities of sustainability and climate change. As one student put it: ‘I don’t know who to talk to about these issues at school’.

Figure 1: Word cloud based on the question of what words the students associate with the future.

During the online event, students had the chance to write down ‘asks’ of the school system, developing ideas for how their school could improve its approach to sustainability. Many of their comments showed a deeper understanding of climate change beyond the content highlighted during the events and displayed a desire for climate change and sustainability to be given more space in the curriculum, with students as content creators.

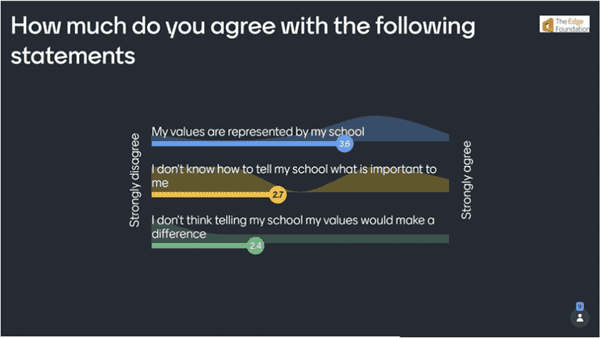

Another dimension of student agency is the feeling of being heard and taken seriously. Three statements were used to gain an understanding of the students’ perspectives about their own voice in the school system:

- My values are represented by my school

- I don’t know how to tell my school what is important to me

- I don’t think telling my school my values would make a difference.

Students gave their level of agreement or disagreement on a Likert scale (Fig. 3), with 1 being strongly disagree and 5 being strongly agree. Analysis showed that students generally believe their values would be considered in the school system if they got the chance to voice them and that their values are being represented by their schools. However, almost half of them also said that they did not know how to address what is important to them at school.

Fig. 2 Likert scale showing students’ perspectives about the three distinct statements.

(The numbers in the circles indicate the average value calculated based on the answers of the students ranging from 1=strongly disagree to 5= strongly agree.)

Future developments

Based on our reflections from the online event, the student event planning team decided to create a more discussion-based approach for the in-person event. The sharing of opinions is important in increasing both reflection and student agency. Creating a safe space for discussion is important for enabling students to develop their communication skills and gain confidence to address topics at school that might be hard to talk about. To accommodate more interactive learning approaches, we designed games that sought to clarify important aspects of communication. For example, two groups of students discussed the question Is a Jaffa cake a cake or a cookie? and had to settle on one answer. Each group had a student referee to guide the discussion and afterward, we discussed their approaches to finding an answer to the question, drawing their attention towards the differences of opinion and the steps involved in finding a resolution.

We also used a visualisation meditation to guide the students through their ideal future school. During the meditation, which I guided, the students imagined their school 5 years down the line focusing on the topic of sustainability and green solutions. Afterward, the students shared their ideas for a future school in small discussion groups.

During the event, students displayed agency in a myriad of ways. Their participation, inquisitive nature, and creativity showed their desire for more in-depth learning in sustainability and climate change education. Schools of Tomorrow and Edge are currently in the process of creating the next Sustainable Education Summit, to be held in Birmingham on November 16, 2023 (https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/redesigning-your-school-to-become-a-more-sustainable-school-tickets-640146935717?aff=oddtdtcreator). After the last two sessions, online and in-person, the organisation team has decided to focus much more on interactive learning in the student session this time around. A big part of the student session at this event will involve students exploring real-life problems their school may face when trying to integrate sustainable solutions. This will be an interactive teamwork exercise, where students have to come up with solutions that please different people in the school, such as other students, teachers, the head, and parents. We aim to inspire the students with this exercise to take a more active role in their schools as well as create a space for self-governed learning and reflection.

To enable student agency to flourish consider the following activities and approaches. Include more activity-based learning that supports reflection and real-life problem solving in your curriculum. Weekly check in circles, in which students get to openly discuss their worries, problems, and things that made them happy during the week can help students reflect on their emotions and work through problems as a community.

Real-life and problem-based activities will increase and improve self-governed learning and creativity in the students. Such activities could be the creation of community gardens, innovation weeks, or cooking societies. These activities will also teach the students skills that they can use beyond the school gates. Activities such as ‘innovation week’, in which students can work on problems they deem important at the school and create their own solutions, will create self-governed learning opportunities, problem solving skills, and can be used to combine different school subjects into an interdisciplinary project.

The world of interactive – and student agency supported learning experiences is a vast one. I hope that some of these ideas will be inspiring to students, teachers, and schools alike. For further ideas and inspiration I recommend the references used in this article as a starting point.

References

- Cavagnetto AR, Hand B and Premo J (2020) Supporting student agency in science. Theory into Practice 59(2): 128–138.

- Corres A, Rieckmann M, Espasa A et al. (2020) Educator competences in Sustainability Education: A systematic review of frameworks. Sustainability 12(23): 9858.

- Duit R, Gropengießer H, Kattmann U et al. (2012) The model of educational reconstruction: A framework for improving teaching and learning science. In: Jorde D and Dillon J (eds) Science Education Research and Practice in Europe. Netherlands: Sense Publishers, pp. 13–37.

- Kangas M, Vesterinen O, Lipponen L et al. (2014) Students' agency in an out-of-classroom setting: Acting accountably in a gardening project. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 3(1): 34–42.

- Niebert K and Gropengiesser H (2013) The model of educational reconstruction: A framework for the design of theory-based content specific interventions. The example of climate change. In Plomp T and Nieveen N (eds.) Educational Design Research – Part B: Illustrative Cases. Enschede, the Netherlands: SLO, pp. 511–531.

- Taub M, Sawyer R, Smith A et al. (2020).The agency effect: The impact of student agency on learning, emotions and problem-solving behaviours in a game-based learning environment. Computers & Education 147: 103781.

- Vaughn M (2018) Making sense of student agency in the early grades. Phi Delta Kappan 99(7): 62–66.

- Vaughn M (2020) What is student agency and why is it needed now more than ever? Theory Into Practice 59(2): 109–118.